| legeros.com > History > Black Fire History > Early Black Firefighters of North Carolina > History of Black Firefighters |

THE HERITAGE OF THE PAST IS THE SEED THAT BRINGS

FORTH

Inscribed on the National Archives building, Washington, D.C.

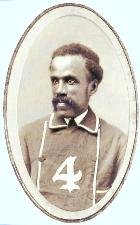

Unknown Black Firefighter 1855-1856, Courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA

| Chuck Milligan 2116 Courtside Lane Apt.206 Charlotte NC 28270 704-847-9314 fireriter@aol.com |

|

and | Rev. Ron Ballew 4225 N. 92nd St. Milwaukee WS 53222 414-463-2662 |

|

This is an effort to pay tribute to the many volunteer and paid firefighters of color. Not in recent years but in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. This time period is chosen because there is little written about these men and in most instances they are forgotten. You are free to use this material in any constructive way. There should be no charge for the use of this material or any profit made from the use of it. For the most part it was freely given and should be passed along the same way. If you have material to add, or changes that should be made, please contact me at fireriter@aol.com .

See Early Black Firefighters of North Carolina .

A portion of this page is included in the book "Firefighters".

In history there is no clear beginning or end. The earliest evidence available puts us in New Orleans, Louisiana in the year 1817 in the month of July. New Orleans had just experienced a devastating fire, fingers were being pointed as to why there had been such a great loss. Action was taken by the governing body to officially organize its people to avoid another conflagration. Fire Commissioners were appointed to take charge at any fire and to conscript any and all bystanders and assign them to service. This included draymen and their equipment as well as individuals both free and slave.

If this did take place consider these as the first black firefighters. This is not to imply that this is the first time a black person ever engaged in firefighting. This is the first discovered document that indicates government sanctioned black firefighters.

In about 1821 volunteer firefighters were being solicited including permission for free men of color to organize fire companies. All of this is very disconnected and vague and does not show these companies being organized.

In 1833 four companies are mentioned, Volunteer No.1, Mississippi No.2, Lafayette No.3 and Washington No.4. This time new equipment had been purchased and placed in use by the Lafayette and Washington companies. The problem was Lafayette and Washington was made up of "two squads of negroes, with a colored man named Johnson at their head." It appears that the other two companies felt they should have received the new equipment and were jealous of the black companies. The white firefighters put on a demonstration in opposition to this action and prevailed. Washington No 4 was reorganized and named Neptune.

There are conflicting opinions as to how long the black firefighters were active. Some feel they were not in existence long enough to ever answer an alarm, however the book this information is based on states that , Washington No.4, "have been in existence prior to July 1834. In that month it participated in the Lafayette obsequies, (Lafayette fire company) and it was also one of the two companies (No. 3 being the other) that were put by the City authorities into the hands of negro's, thus bringing about the remonstrances and successful opposition on the part of the older companies, which finally brought the companies together under one general association for mutual purposes, out of which grew the Firemen's Charitable Association. "Reference to "Lafayette obsequies" gives even more credence to the fact that these two companies were a viable part of the fire department. The definition for obsequy is: a funeral or burial rite. This would lead you to believe that they had buried one of their own.

Source: History of the Fire Department of New Orleans edited by Thomas O'Connor, Chief Engineer, 1895

Restored Hose Reel displayed in Oklahoma City Fire Museum

In 1818 a group calling themselves the African Fire Association met to complete plans for forming a fire and hose company. A meeting was held and officers of the organization elected one of them being Derrick Johnson president and the other Joseph Allen secretary. A committee for soliciting subscriptions was appointed. Some of the circulars that they were using to promote their organization fell into the hands of white firemen.

This brought about a conference of the white fire companies the meeting held at a place called Stells Tavern. About twenty-five companies were represented. A resolution was passed reading: "The formation of fire-engine and hose companies by persons of color will be productive of serious injury to the peace and safety of citizens in time of fire, and it is earnestly recommended to the citizens of Philadelphia to give them no support, aid, or encouragement in the formation of their companies, as there are as many, if not more, companies already existing than are necessary at fires or are properly supported" The committee was appointed at this meeting to see to it that authorities did not allow them to open fire plugs. Another meeting was held on the 13th of July, with even more companies attending. Here the committee reported that they had contacted the watering committee on Councils and that they said they were required to grant a license to any fire association applying for the use of the plugs to fight fire.

Before things could get out of hand some of the "persons of color" had a meeting at the home of George Jones. James Forten chaired the meeting and Russell Parrott was secretary. They had heard how upset the white firemen were and wanting to avert trouble passed the following resolution.

"A few young men of color had contemplated the establishment of a fire or hose association, and, although the same may have emanated from a pure and laudable desire to be of effective service in assisting to arrest the progress of the destructive element, we cannot but thus publicly enter our protest against the proposed measure, which we conceive would be hostile to the happiness of people of color, and which as soon as known to us, we made every effort to repress. Should it be carried what effect we cannot but consider that it will be accompanied with unhappy consequences to us. Therefore we sincerely hope that supporters of the contemplated institution, and such as might wish to be concerned, will relinquish all ideas of the same" The African Fire Association met again on July ,19th and decided the whole idea should be abandoned. A resolution was passed that amounted to an apology to the whole community for having upset anyone as that was not their intention.

There are a number of race riots recorded in Philadelphia in the first half of the nineteenth century and this may have been the reason for the quick change of mind. On May 18, 1838 an orphanage for colored children was burned. It should be noted however that not all of the white fire companies were in open opposition.

Joseph A. Marshall, a retired lieutenant of Engine 11 documented some of the history of the early black firefighters of Philadelphia. The book is tilted “Leather Lungs" and is written in 1974. The book focuses on black fire fighters but also highlights one individual who was nicknamed “Leather Lungs.” This term has been used in the old days to describe men who seemed to be able to breath the smoke with out having to come out for air. These men had their own secret for being able to withstand the punishment of heat and smoke. One trick was to place your nose as close to the hose stream as possible there was a small quantity of fresh air around the stream.

In his book Marshall tells of the first paid black firefighters. The department went to full paid December 29, 1870. He does not say if there were black volunteers prior to that. On April 13, 1886, Isaac Jacobs was appointed and assigned to engine 11. He stayed just over four years. Less than a year later Stephen Presco was appointed and was killed while on duty on March 7, 1907. Others followed and left their own mark on the history of the department.

It may be well to note at this time that the Marquise de LaFayette at the young age of 19 he had come from France to the Colonies, in 1777 to assist in the efforts to free them from the British. LaFayette became a dear friend of George Washington during the following years of combat. He had given a plan to Washington for freeing the slaves and on returning to France formed the Society of The Friends of the Blacks. His goal was equal rights for all people. He returned to American in 1825 and drew large crowds as he toured the new United States of America. One person that greeted him on his return was James LaFayette.

James LaFayette had been born in slavery in 1748 in Kent County, Virginia. When LaFayette came to America to help in the war effort James ask his master for permission to join with the Marquis. They became fast friends as James infiltrated the enemy camp acting as a servant in the headquarters of both Benedict Arnold and Lord Cornwallis. Cornwallis was so impressed with James that he sent him to spy on LaFayette. At the surrender of Cornwallis he discovered James in the headquarters of LaFayette in the uniform of an American. The information he was able to gather as a spy was invaluable to LaFayette. At the close of the war the General wrote a certificate praising his work in the war effort. James forwarded his certificate to the Virginia Legislature asking for his freedom. His freedom was granted and he took the name of LaFayette as his last name.

The French General had endeared himself to all who heard about his exploits during the Revolutionary War. His efforts to claim freedom for blacks no doubt was the talk of the black community.

[ image missing ] [ image missing ]

[ image missing ] [ image missing ]

The photo at left is from Charleston, West Virginia meeting of fire fighters about 1880-1900.

The center photo is a young firefighter from a collection of Hank Bergson while the one on the right is from a collection of Mike Novak.

By Stanley Levine

In 1824 the first real improvement in the fire service took place. An act was passed by the General Assembly by which the City of Savannah was invested with the power to appoint twenty-one firemen. This was the first regularly organized fire department in the city. All of the engine houses, engines, ladders, buckets, hose and other implements were turned over to the Savannah Fire Company. This body elected their own chief fireman, first fireman and second fireman, subject to the approval of Council. No salaries were paid, and all vacancies by death, resignation or otherwise were filled by Council upon recommendation of the fire company. The Savannah Fire Company made their own by-laws and rules, and had the right to expel any of its members for violation of company rules, or city ordinances. They were authorize to employ a clerk at a salary of $8.00 per month. The work at fires was performed by "free men of color, free negroes and hired slaves." The City Scavenger "on the breaking out of fire", was required to "order his carts at different places where the public buckets, fire hooks, ladders and other implements for the extinguishment of fires are kept, and to assist in carrying the same to the fire or to such place or places as may be directed by the firemen."

Robert Campbell was chosen the first fire chief, and four new hand engines. reels and the necessary quantity of hose was purchased.

The ordinance of March 11th, 1825, provided that the City Marshal "immediately take an account of the colored and negro firemen between the ages of sixteen and sixty and make a return of the same to the Chief Fireman." Each enrolled free man of color was required to furnish himself with a cap or hat" on which shall be put the initials F.C., to be worn when ever he is on duty. " If any enrolled free man of color or free negro failed to answer an alarm they were subject to a fine in a sum not exceeding ten dollars, or be imprisoned in the common jail for a period not less than five nor more than fifteen days. Free men of color and free negroes enrolled as firemen were exempt from poll tax. Once a month the free men and slaves were ordered out "for the purpose of playing off the engines and drilling in the use of them, cleaning and keeping in good condition the ropes, buckets, hose, ladders engines;" and any failure to attend these drills subjected the offending party to a fine not exceeding ten dollars or imprisonment not exceeding fifteen days. Any member of Savannah Fire Company was authorized to order any citizen to "assist in the filling of the engine with water during a fire and otherwise render assistance;" and should any citizen refuse to obey such orders any member of the fire company was authorized to arrest him, bring him before the Mayor or any Aldermen present, who was authorized to send him to the guard house until the next day, and on conviction he would be liable to a fine not exceeding thirty dollars; and the Clerk of Council " Shall, when directed by Council., publish his name in the public gazette of the city at least once."

The City Marshal and the constables were required to assemble at all fires with their staves of office and report to the Mayor, Chairman or any Alderman present.

The ordinance required the Mayor and Alderman to assemble at each fire to enforce the ordinances. It was a violation of the law for any one to ride in or through any street, lane or square in which the inhabitants were assembled for the purpose of extinguishing fire, except the commandant of the militia and his staff, and then only when it became necessary for him to communicate with the Chief Fireman.

"To prevent, as much as may be, the great confusion which may arise from too many men armed at the time of the fire, the Mayor was directed to request the commandant of the militia to fix the number of men necessary to be under arms by a routine, once in every three months."

In March, 1825, an ordinance was enacted requiring any fireman of the fire company who shall contemplate an absence from the city for a period longer that one month to furnish a substitute satisfactory to the Chief Fireman.

During the same year a special tax was levied by ordinance, requiring the payment of ten cents on every hundred dollars on the value of improved real estate for the purchase of engines, hose, ladders, etc.

In August a wooden engine house was built in Liberty Square.

In 1825-27 the fire department had regular parades and inspections on the last Saturday in each month. Twenty slaves were allowed to each company, and each slave was paid fifty cents for every parade.

At this period any person sounding a fire alarm "by ringing of bells or the beating of drums" received a reward of such an amount as was agreed upon from time to time by the fire company. This was abolished in March of 1836. The Savannah Fire Company was divided up, and one or more of its members were assigned to the management of the negro firemen of the different engines; these members were known as "Masters of Engines," and were authorize to have administered "prompt and immediate correction" whenever a slave "disobeyed or otherwise offended." Each slave fireman was provided with a badge, which entitled him to the "immunities and privileges of a fireman."

In 1826 an engine house was built in Franklin Square. On May 25th, 1826 "it appearing to Council that the number of free persons of color returned to the fire company by the City Marshal are not sufficient towards a complete reorganization of the fire department of the city," an ordinance was enacted providing for the enrollment of a greater number of negro slaves and the payment of twelve and one-half cents per hour while engaged in drills or at fires. The first slave firemen who arrived at the engine house on an alarm of fire received one dollar and the second and third received the sum of fifty cents each, and upon the failure of such slave to answer an alarm he forfeited one hours pay for every fifteen minutes he was late, and when such fines exceeded the value of his badge he was deprived of the same and lost the privileges enjoyed by its possession. In July. 1826, Council enacted an ordinance providing for the distribution of rewards, amounting to thirty dollars for each fire, to be distributed by the Chief Fireman, or in his absence the Directing Fireman, "for the encouragement of free persons of color, free negroes and hired slaves, who may be active in carrying engines, etc. to extinguish fires." So far as can be ascertained, the department at this time consisted of seven hand engines, with the necessary hose and other implements. The department was operated in what might be called a successful manner, and the fire loss was held down to a degree reasonable with the facilities at the command of the Savannah Fire Company.

The report of Chief Fireman Parker on January 11th, 1827 showed the city then had "two suction engines, one suction and discharging engine, 1,200 feet of ladders, one Philadelphia built engine, one Boston built engine and one hose cart, all in superior order and efficiently officered and manned." There was also a Boston built engine in good order and a quantity of useless machinery. The effective labor required, he stated, was about 300 men. The current expenses were placed at $1,200. Every alarm for fire cost $25.00. Six useless engines were sold for $570.00.

In 1828 the department consisted of four New York built suction and discharging engines; two London built suction and discharging engines; two Boston built engines, one hose cart, 1,740 feet new hose, 700 feet of old hose, 178 slaves, 96, free negroes, 274 buckets, 15 fire hooks, 44 ladders, 22 axes and a white company of seventeen men.

Early in the "30s" the frame engine houses began to disappear and substantial brick buildings took their place. Some of the new houses wee two stories high, the upper floor being used for meetings and gatherings of the members of the company. In 1834 an engine was bought at a cost of $700.00 and a brick house was erected in the northern part of Oglethorpe Ward for the same.

In 1845 the young men of the city began to take an interest in the fire department and on February 19th, 1846, Council approved an application from a number of young men for a charter as the Oglethorpe Fire Company of Savannah. The number of members was limited to fifty. They were to supply their own apparatus within a year, were to work in themselves, were to enjoy the same privileges as the Savannah Fire Company and be under the Chief Fireman.

In 1847 the Washington Fire Company was organized and in the latter part of the following year the Young America Fire Company sprung into existence. This latter company was made up of the rough element of the community and gave the officers and members of the Savannah Fire Company great trouble and annoyance. At almost every fire the Young Americas engaged in a fight with someone and on a number of occasions they drove the faithful slaves away from their posts of duty.

In May of 1850 the Savannah Fire Company adopted resolutions to allow colored firemen to wear uniforms. The Oglethorpes and Washington's protested against this resolution as degrading to the white firemen and the Council directed the Mayor not to permit it, later, however, Council reconsidered this action and left it to the Savannah Fire Company to do as it wished.

The Savannah Newspaper had this to say in its May 28th ,1853 issue:

"Yesterday the Savannah Fire Company paraded. It was reviewed by His Honor the Mayor and the Chairman of the Fire and Water Committee of Council.

It is a subject for extreme gratification to our citizens, to witness so imposing a display of real stamina and solid worth, as this parade afforded. Some four hundred stout fellows, the pick of the colored population, devoted to the protection of the city from the ravages of the devouring element.

Their engines, lanterns, torches, etc., were gaily and most tastefully arrayed in fresh flowers and ribbons, and the men themselves, all uniformed according to the dress adopted by their respective companies.

The line consisted of seven engines, two suctions, one general hose-cart, one bucket company, and one hook and ladder and axe company.

After being reviewed by the Mayor, they were dismissed and returned to their respective quarters."

June, 1853, more trouble between the Savannah Fire Company and the Oglethorpe Fire Company over the latter's mistreatment of negro firemen at fires. The Councils Committee on Fire reported at the close of the year there was utter disorganization of the department. Early in 1854 more trouble occurred. The Council had given Oglethorpe Fire Company control of its engine and authorized it to appoint its firemen subject to the approval of the Mayor and Aldermen, instead of the Savannah Fire Company. The Savannah Fire Company claimed that the Oglethorpe Fire Company was beyond control of the Chief Fireman and proper service could not be secured from them. After much discussion the Savannah Fire company resigned in a body, publishing their resignation in the local paper before sending it to Council. The resignations were accepted November 9th and a new company was promptly appointed.

The dispute between Savannah Fire Company and Young America Company finally came to an end and the latter was disband.

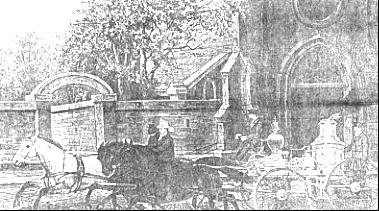

These two men are Savannah Firefighters of this period. Courtesy: Special Collections Department, Robert W. Woodruff Library Emory University.

1856 found Savannah protected by, Oglethorpe No 1, 35 members (white) Washington No 9, 52 members (white), Germania No. 10, 48 members (white), Axe, Hook and Ladder, 2 white officers and 50 free men of color, Engine One, two white managers and 80 slaves, Engine Two, 2 white officers and 79 slaves, Hose One, one white manager and 21 slaves, Hose Two, one white manager and 25 free men of color. Engine Three, two white officers and 60 slaves, Engine Four, two white officers and 65 free men of color, Engine Eight , two white officers and 78 slaves, Engine Eleven, two white officers and 78 slaves.

1860 White companies were Oglethorpe, Washington, Geranium and Mechanic Hook and Ladder. Colored Companies. Warren Hand engine, Pulaski Hand engine, Franklin Hand engine, Neptune Hand engine, Tomo-Chi-Chi Hand engine, Niagara Hand engine, Wild Car Hand engine, Columbia hose, Hose #2 and Axe Co #1.

Note: A large number of people was required for each "engine" and Hook and Ladder, as these were all hand drawn wagons and upon reaching the fire the pumps were manned by manual labor. One advantage the black man had over the white was that they had learned from years of heavy labor to combine their energy with rhythmic chants or songs and no doubt the firemen sang or chanted as they manned the hand pumps much as the stevedores when loading ships and the gandy dancers while driving rail spikes.

In a book titled “The Fireman:” David D. Dana gives information about a number of fire departments in 1858. On page 229 he had this to say about Charleston:

"There are in the department ten engines manned by whites, and ten manned by negroes, who have white presidents, who are responsible for the apparatus under their charge. The individual members receive no pay, but the engine which puts the first stream upon the fire receives a premium of twenty-five dollars; and all of the white companies receive sixteen dollars per hour while working at fires.---------The companies are not limited in regard to the number of men for each company."

This information as well as other information on this site was kindly furnished by Tom Scott.

Dana does not say that Mobile had black firefighters however the Ordinance establishing the fire department in Section 8 describes the manor of electing officers states that "the qualified voters and white firemen of the several companies" elect the officers. Had there been no black firefighters it is not likely this wording would have been needed.

THE FIRST BLACK FIRE CHIEF IN THE UNITED STATES

CAMBRIDGE MASSACHUSETTS

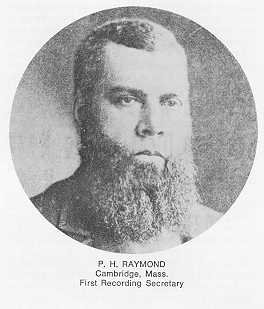

Patrick H. Raymond was born in 1831 and was appointed to the fire department in the early 1850's, assigned to "Hydrant Engine Co. No. 4." He was appointed Chief Engineer (Chief of Department) of the Cambridge Fire Department on 5 Jan 1871. He was pensioned on 17 April 1879 and died on 28 July 1894.

Chief Raymond is believed to be the first Black Fire Chief in the United States. Chief Raymond was also a member of the National Association of Fire Engineers (predecessor to the International Association of Fire Engineers and the International Association of Fire Chiefs) and held the office of Recording Secretary in that organization from 1873 to 1877. Engine Company #5 in Inman Square (1384 Cambridge St.) was organized on 30 Nov 1874 and was named "Patrick H. Raymond Steam Engine Company #5." in honor of Chief Raymond. The company is still in service today in a newer (1914) firehouse at the same location.

The photo was scanned from the Centennial History Book of the International Association of Fire Engineers, published in 1973. The historical information was written by retired Cambridge Chief of Department William J. Cremins and comes from the same book and also the records of Capt. Steve Persson of the Cambridge Fire Department.

This information comes from John Gelinas, Deputy Fire Chief, Cambridge Fire Department, 12-22-99

AND THEN THE WAR

1858 was the beginning of a paid department in Richmond. After a long discussion, the City Council, in the fall of that year permitted the hiring of 10 slaves for each company. The requirements were that they be of good character. These men were to man the hand pumps then in use. The beginning of the end of hand drawn equipment meant that it would take less manpower to get the equipment to the fire and now the horses began to appear on the scene. Even as the Confederate Capital could almost smell the smoke of Yankee guns it had to protect its self from fire. A new steam engine in late 1863 required a skilled hand on the reins of the horses. Most southern young men had gone to war and someone was needed now. The City Council Fire Committee on January 5, 1864 authorized the hiring of two black firefighters. One was hired as a hostler while the other was to tend the stream engine and stoke the fire.

History of Blacks in Richmond Fire and Emergency Services

In 1858, a paid fire department was organized in Richmond, Virginia. It consisted of six commanders, six foreman and 90 firefighters. This Fire Brigade was placed under the supervision of a City Council Committee. On October 25, 1858 City Council authorized each company to use 10 slaves "of good character" to man the pumps. During this time a movement to replace hand-pumped engines with steamers gathered force. On January 5, 1864, the Council Fire Committee authorized the Fire Brigade to select one Negro man to act as hostler (a person who takes care of horses) and one Negro man to serve as a fireman (a person who fires and lubricates steam locomotives) for a steamer fire engine. It was May 5, 1950, when a local paper announced that the city personnel department would soon set in motion operations for the recruitment of Richmond's and the State of Virginia "first ten Negro firefighters." On July 1, 1950, the department hired its first "Negro" firefighters to form the first black unit in the city. The plan called for the men to work under white officers until they could qualify for promotion. Ten men were selected from 500 applicants. They were as follows: Charles L. Belle, William E. Brown, Douglas P. Evans, Harvey S. Hicks II, Warren W. Kersey, Bernard C. Lewis, Farrar Lucas, Arthur L. Page, Arthur St. C. John, and Linwood M. Wooldridge. Arthur C. St. John was called to return to the military in 1950 and Frederick J. Robinson was hired. When Farrar Lucas resigned in 1951 Oscar L. Blake was hired. The black firefighters would man Engine Company 9 at Fifth and Duval streets "in the heart of a Negro residential and business district."

The qualifications for Negro firefighters were the same as for the white firefighters. However, white recruits would go immediately to the fire stations for company assignments and into regularly scheduled training classes, whereas a special training program was required for the Negro firefighters. The black firefighters were going into a single company house as a unit and under the leadership the "Drill Master" had to be completely trained in every detail before they could function as such. The black firefighters were trained for two months, twice the required time for white firefighters. Part of the reason the training was so long was the department erected separate sleeping quarters and bathrooms to house the four white officers and two white engineers. Black firefighters got most of the assignments to fight the constant dump fires and had to wash and clean the hoses for their own companies after a fire and sometimes for some of the white units at the scene. They were required to wash all the equipment after every run (while white companies washed equipment near the end of the shift). This meant that if they had six calls during a shift, they washed all the equipment six times. They were also required weekly to wash down the walls of the fire station from top to bottom, a task that white companies were not required to do. Black firefighters had to wear full dress uniforms (hat, coat, tie, dress shirt and pants) if they wanted to sit outside of the fire station. Therefore, if a fire call came and they were outside, they had to answer the call in dress uniforms. Other companies were not required to do this.

The men of Engine Co. 9 were often given the chores nobody else wanted. Members were called to City property when grass needed to be cut, buildings needed to be painted, or hornets' nests needed to be removed. They also drove the service truck from station to station collecting damaged equipment and delivering laundry and supplies. They could not go into three of the city's fire stations, (6, 13, & 19). Instead they would go around to the back of the stations and knock on the window and white firemen would bring their laundry to the driver. One of the white captains said "They are good firefighters under proper leadership and they are doing well learning to drive the equipment". "On one or two occasions, he said that nervousness and over-eagerness hindered them". Despite feeling as though they were being treated like second-class citizens, they made up their minds that they would be the best firefighters the City had. They were the first group to be trained as a company; they could go into a fire and put it out scientifically. Although being college graduates or having some college, the black firefighters of Engine Co. 9 were better educated and better trained than most of the City firefighters. But they were not afforded the same opportunities as their white counterparts.

Normally, it took three years to qualify for an engineering position (driver/pump). However, when some of the members of Engine Co. 9 became qualified for the job, the position was mysteriously eliminated. Firefighters at Engine Co. 9 always scored in the top 10 in examination scores, however, because of segregation they were not allowed to supervise white firefighters. Therefore, unless there was a vacancy in Engine Co. 9 there were no promotion opportunities for black firefighters. Black firefighters were placed on promotion lists until the lists expired. Harvey S. Hicks was promoted to Lieutenant in 1955 and was assigned to E-9 and promoted to Captain in 1961 and assigned to E-9. Linwood M. Wooldridge was promoted to Lieutenant in 1956 and assigned to E-9. Oscar L. Blake was promoted to Lieutenant in 1959 and also assigned to E-9. Arthur L. Page was promoted to Lieutenant in 1961 to replace Lt. Harvey S. Hicks and was also assigned to E-9. Charles L. Belle was promoted to Lieutenant in 1967 and was assigned to E-9. Charles L. Belle passed the Lieutenant's examination in 1956 but had to take the test 10 more times before he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant in December, 1967.

The black firefighters remained segregated at Engine Company 9 until 1963. A tragedy struck in 1963 that caused the department to take another look at segregation. On June 14, 1963 Captain Harvey S. Hicks, Douglas P. Evans and Calvin Wade attempted to rescue a self-employed contractor from a 23-feet deep pit. When the three failed to return, Herman Brown went down to see what had happened and saw that all four men had passed out. Feeling weak himself, Brown climbed back up the ladder. Lt. Oscar Blake went down next. Having just enough strength to pull off his mask, Lt. Blake climbed back up the ladder. By that time other firefighters had arrived. Using air packs they brought Wade up, administered oxygen and he regained consciousness. All Wade could remember was Captain Hicks was giving artificial respiration to the contractor. Captain Harvey S. Hicks, Firefighter Douglas P. Evans and the contractor were pronounced deceased on arrival at St. Phillip's Hospital. Captain Harvey S. Hicks, the department's highest-ranking black officer and firefighter Douglas P. Evans suffocated in this rescue attempt of a contractor who was also a good friend of the firefighters. Since all the black firefighters were stationed together it was possible that a major catastrophe could possibly wipe out the company.

After 13 years some type of action was taken to integrate six of the department's 28 companies with the departments' 13 black firefighters. Two black firefighters were assigned to each of the six fire companies and one assumed a fire communications position. On July 6, 1963 Bernard C. Lewis and Charles L. Belle Jr. were assigned to Engine Co. 5. William W. Kersey and Herman O. Brown were assigned to Engine Co. 17. Roscoe W. Friend and Frederick J. Robinson were assigned to Engine Co. 12. Robert L. Myers and Calvin Wade were assigned to Engine Co. 11. Ralph Hutchins was assigned to Truck Co. 4. After a temporary assignment working out of the Chief's office, another first for Blacks, Arthur C. St. John was assigned to the fire communications center in Monroe Park, which also was another first assignment for blacks. Lt. Oscar L. Blake and Lt. Arthur L. Page remained at Engine Co. 9 under a white captain and over the white firefighters transferred to Engine Co 9. The black firefighters had consistently demonstrated competency and commitment to the department while battling subtle discrimination. Fire station No. 9 was built in 1902 and demolished in 1968. On Saturday, July 1, 2000 the Southwest Corner of 5th and Duval Street became a historical highway landmark.

Outside of Richmond many black firefighters nationwide began to demand equal rights also. On October 3, 1970 the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters (Keep The Fire Burning For Justice) was founded. Black Brothers Combined joined the International Association of Black Professional Firefighters later. In 1974, under the combined efforts of Theodore Fuller, Roscoe Friend, Norville Marshall, James Duke Stewart III, Everette Jasper, Alvin Mosby and others, Black Brothers Combined Professional Firefighters of Richmond, Virginia Inc. was formed. James "Duke" Stewart, Jr. was Black Brothers Combined (BBC) mentor. The group was formed to ensure equality within the fire department. They established as their motto, "To Obtain the Unattained." At its inception the bureau had only one black Lieutenant, Charles L. Belle, one black Captain, Arthur L. Page and approximately 78 black firefighters . On July 17, 1974, BBC initiated a class action job discrimination lawsuit. The lawsuit charged racial discrimination in hiring assignments, transfers and promotions. In March, 1977, a federal judge issued a preliminary injunction barring further permanent promotions in the fire bureau until the lawsuit was decided. A judge ruled against the black firefighters and a federal judge upheld the decision in December, 1978, one month after the arrival of the bureau's first black chief, Ronald C. Lewis.

The hiring of the former Philadelphia Battalion Chief was historic for another reason. He was the first top man who did not rise through the ranks of the Richmond Fire Bureau. Under Chief Lewis' command a 60-hour workweek dropped to 56 hours, modern equipment replaced old apparatus and firefighters received new uniforms. Chief Lewis headed a department of 510 employees and protected 62.5 square miles. Also under his leadership, a highly skilled river rescue team was developed, a Hazardous Materials Unit was created and the Fire Information Management System, which computerized all information in the department, was installed. Even though the discrimination lawsuit was dismissed by the court system, the City of Richmond made significant changes in the hiring and promotion process within the Bureau of Fire. On December 26, 1979, Captain Arthur L. Page was promoted to Deputy Battalion Chief. He was the first Black to rise through the ranks from firefighter to Deputy Battalion Chief where he worked until his retirement. On Sunday, February 10, 2002 during Black History Month, Deputy Battalion Chief Arthur L. Page was honor at his church by family, friends and co- workers for his accomplishments throughout his fire department career and life. A portrait of Chief Arthur L. Page, was commission by James "Duke" Stewart, III and unveiled by Arthur C. St. John and Fredrick J. Robinson.

On November 3, 1979 history was made again in the Richmond Fire department, Barbara J. Hicks-Spring the first female and first black female firefighter was hired. On July 11, 1988 Tina Watkins was hire as the second female and second black female firefighter. She was promoted to Lieutenant on September 20, 1997. With this appointment, Lt. Watkins was the only female officer and the first female in Fire Prevention. Tina Watkins was appointed to Captain on May 3, 2003. Deputy Battalion Chief Page and others like him led the way for Division Chief John E. Tunstall, Division Chief Larry Tunstall, Division Chief Alvin Mosby, Battalion Chief Norville Marshall, and Battalion Chief Everette Jasper and others to rise to the top ranks within Fire and Emergency Services department today. They began their careers in the Richmond Fire Department as firefighters and through the years they worked their way up through the ranks with hard work, determination and dedication to be promoted. John E. Tunstall has risen through the ranks from firefighter to Fire Marshall Chief. He became a firefighter August 17, 1970. During his years in the department, John was promoted to Lieutenant in February 1976, Captain in January 1979, Deputy Battalion Chief on March 17, 1984, Battalion Chief in 1986 and Division Chief in 1987. John was the first to serve as Fire Marshall Chief, one of the top four positions in the department before moving on to the City of Hopewell, Virginia. John is currently the Chief of Hopewell fire department, the first African American to hold this position, making history again.

Larry R. Tunstall, a 34-year veteran, was the first to serve as Chief of Operations/Administration, another of the top four positions of Richmond Fire and Emergency Services. He was hired as a firefighter on September 29, 1969. Larry was promoted to Lieutenant in February 1976, to Captain in May of 1979, Deputy Battalion Chief in 1984, to Battalion Chief in 1987, to Division Chief on June 10, 1998, and Fire Marshall Chief on August 26, 2002. On September 12, 2003 Larry was appointed Chief/Director of Fire and Emergency Services. Larry R. Tunstall is the first African American to come through the ranks to the top position. Alvin W. Mosby Sr., a 35-year veteran, has risen through the ranks from firefighter to become Chief of Operations/Administration. He was hired as a firefighter on November 20, 1968, promoted to Fire Inspector on April 26, 1976, Lieutenant on November 2, 1979, Captain on September 17, 1983, Battalion Chief on October 3, 1987 and on August 26, 2002 was promoted to Division Chief of Operations/Administration. This is another of the top four positions of Richmond Fire and Emergency Services.

Joseph Jenkins Jr., a 33-year veteran is currently serving as Commander of Training Academy was hired on April 6, 1970 as a firefighter and later promoted to Lieutenant on June 25, 1983 and to Captain on October 7, 1989. This is another of the top four positions of Richmond Fire and Emergency Services. Don J. Horton, a 23-year veteran is currently serving as Acting Fire Marshall Chief as of August 2001. Horton was hired on April 31, 1980, promoted to Lieutenant on October 3, 1987, Captain on April 21, 1990 and Deputy Fire Marshall on May 5, 2001 and currently appointed to Battalion Chief on April 1, 2003. Making this the fourth top position held by African Americans.

Over the years Richmond has seen many changes, with the name change from the Richmond Fire Department to Richmond Fire and Emergency Services. On November 1, 2000, Black Brothers Combined Professional Firefighters Inc. (BBC) changed its name to Brothers and Sisters Combined Professional Firefighters, Inc. (B&SCPFF). on May 3, 2003 there were 14 African Americans promoted to the rank of Lieutenant and 4 promoted to the rank of Captain. This was the first time in the history of Richmond Fire and Emergency Services that this many promotions of African Americans were made simultaneously. Our brothers who started us out have stayed together and have now formed a retired firefighters group called Engine Company # 9 and Associates, thus showing us that we must continue to stand together within as well as after retirement. Although we have African Americans in the four top positions of Richmond Fire and Emergency Services, as the journey continues, we must not stray from our goal "To Obtain the Unattained". With Unity and Strength, the goal of "To Obtain the Unattained" can be reached.

Hand drawn Chemical Cart: Oklahoma City Fire Museum

Charles W. Borden

The City of New Bedford is located on the south coast of Massachusetts, about 50 miles south of Boston. The area was first settled in 1652 and was originally part of Dartmouth. The original settlers were Quakers and Baptists who fled Plymouth Massachusetts because of religious persecution at the hands of Puritans.

In the mid 1700s Bedford Village, as it was then known, was a small whaling village on the west bank of the Acushnet River. As the demand for whale oil grew, so did the whaling fleet which sailed out of New Bedford. By 1823 New Bedford was the largest whaling port in the United States. The population of New Bedford has always been diverse. The early settlers, the Quakers and Baptists, sought freedom of thought and action. They were very open to people of other religions and nationalities. In the late 1700s free Africans began coming to New Bedford as seamen on whaling ships. Many of them became harpooners. Although there were some slaves in the early and mid 1700s, the moral and religious feelings of the town were strongly against such practices. In 1785, not a slave was held in the town and in 1783 taxpaying blacks had the right to vote. Before and during the Civil War, New Bedford was an active station for the underground railroad. Through the port of New Bedford, hundreds of slaves were led to freedom. The Quakers were concerned for all people. They were against violence, and in New Bedford all blacks were safe, protected by whites and blacks alike. Frederick Douglas, the great writer, politician, orator and abolitionist, was received in New Bedford in 1837 as a runaway slave. He worked for many years on the docks and left in 1841. He influenced an entire nation and helped to put an end to slavery.

The New Bedford Fire Department was organized in Jan.30, 1834. At this time it was an honor to be a fireman and many politicians and businessmen were members. The Department consisted of six pumpers, which were operated by hand and one ladder truck. In April, 1842, members of the department were paid $10.00 a year for their services. After a major fire destroyed the center of the city in 1860, the department began to change from the obsolete hand pumpers to the new steam engines.

Charles W. Borden was born a free man in Westport, Massachusetts. As a young man he moved to New Bedford and lived at 30 Bedford St., near fire station no.4. He was the first African American Firefighter on the New Bedford Fire Department. He joined the Fire Department on Nov.9, 1868, and was assigned to Steam Engine Co.No.4, the "Cornelius Howland." stationed at Bedford and Sixth St. in the south central part of the city. He was a paid member of the department and was assigned the duties of hose reel driver. Apart from the fire department, he worked as a hostler. After 15 years of service, he left the department in 1883.

Thomas J. Marginson, New Bedford Fire Dept.

Special thanks to Larry Roy, Curator, New Bedford Fire Museum" for his expertise and Chris Anderson at Reale Image Specialty Design for the photo enhancement.

SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

By Shirley F. Lerner

Civilian firefighting in San Antonio was brought to a near halt during the Civil War. Most of the volunteers from its two fire companies entered into military service and went away to do battle. Firefighting in San Antonio was left to the Confederate soldiers who were stationed in the city, to slaves, and to a handful of remaining volunteers. At war's end, the Milam Company No.1 and Alamo Company No.2 were nearly decimated. Only 10% of the Milam's 82 charter members survived the War. Records of Company No.2 do not indicate numbers lost to battle, but it is safe to assume that they also suffered numerous casualties.

When hostilities ceased, a reorganization of the two companies was obviously necessary. Within a few years, civic minded individuals replenished the ranks and the two groups once again functioned at full force. The repopulated organizations then set out to re-equip their personnel. San Antonio was in a financial bind during Reconstruction and could not afford significant modern machinery for its firefighters. Consequently, William A. Menger, chief of Company No. 2, gave the city its first steam pumper on June 12, 1868. He purchased it for $4000.00 from a company in New York, paid for its shipment, and had it hauled to San Antonio from the Port of Galveston. The Milam Company on the other hand did not acquire a steam pumper until 1875. This purchase, augmented by Mayor French, was paid for with City funds. The seven year hiatus between the time Co. No.2 acquired a steamer and Co. No.1 had none must have caused some heated incidents between the rivals. The enhanced firefighting advantage produced by Menger's engine made his company more efficient than the Milam. Although there are no documented scuffles between the two organizations, it is safe to assume that some jealousy must have occurred as a result of the disparity.

On January 29, 1869, the San Antonio Turn Verein, an athletic club, organized an additional fire company. On May 30, 1871, the Turner Hook and Ladder Company was chartered. Until a paid fire department was established, this company served the community well.

Interestingly at the Civil War's end and one year prior to the re-organization of the two original fire companies, two new groups of volunteers, Companies No.3 and No.4. were formed. They were comprised of black men who were either freedmen or were former slaves of the Confederate soldiers serving in San Antonio. Very little is known about Company No. 4 except for the fact that it began in 1866, it never applied for a charter, and disbanded, quietly, in 1881. A little more is known about Company No.3 because it was lauded for helping Alamo Co. No.2 during the "Alamo Fire" in 1874. San Antonio Directories list the names of the officers of the two companies. A further check of the personnel indicates that these volunteers were employed as messengers, wagon drivers, or common laborers. Only one man, Jasper Thompson, held a more distinguished professional position. He was the proprietor of the barber shop in the Menger Hotel . With perhaps some guidance from William Menger, Thompson founded Company No.3 and served as its foreman. In their book, The San Antonio Fire Department- 1854-1976, Frank and Genie Myer mention that the local Freedman's Bureau had a hand in establishing the black fire companies. No documents can be found, however, to substantiate the claim.

The saga of the "colored" volunteer fire companies is a significant addition to the history of Reconstruction and it's aftermath in San Antonio. Since volunteer fire companies enjoyed considerable prestige and political influence, it is likely that local blacks were attempting to acquire these goals by organizing fire companies. Little is known about these groups because the general population in the city resented and ignored them. At the time of their inception, the two original fire companies were struggling to re-organize. Some felt the newly established black brigades were a detriment to the re-building of the Milam and Alamo Companies. Nevertheless, the two black volunteer organizations remained long after Reconstruction's end. In 1873, seven years after its founding, a charter was granted Fire Company No.3 during Mayor Giraud's administration. This action is significant because it shows that the white community had accepted some black progress. Perhaps a few of the councilmen had formed political ties with the black community. From then on, however, City Council records and newspaper articles make little mention of Fire Company No. 3.

The idea that there were political ties between the black volunteers and some white leaders is furthered by the fact that companies No. 3 and No. 4 selected two prominent whites to represent them when City Council elected a fire chief in 1878. J.H. Kampmann, a well known businessman and alderman, was chosen by Co. No.3 and Edward Braden, a government contractor and future chief of Co. No.1, was selected by Co. No.4. It is true that negative attitude toward blacks disallowed their rightful self-representation in the election, but obvious political ties with important urban leaders permitted some recognition by the white community.

During the two decades of the black fire companies' existence, the City Council did not provide funds for them. At their request, the white volunteers were continually granted monies for equipment and maintenance. City records indicate that Companies No.3 and No.4 did not ask for funds until 1886 when Company No.3 requested assistance. Perhaps the city had prohibited them to file such petitions in the past. Whether or not their equipment was up to par, or whether or not they accepted private funds are unanswered questions.

After Co. No.3 requested money from City Council on December 6, 1886, the Fire Committee suggested that the company no longer "warrants continuance" and moved to disband it. Apparently, as soon as the blacks threatened to become a financial burden, their public service no longer had any value. By 1888, Fire Company No.3 was but a memory of the Reconstruction Era.

Hand drawn Hook and Ladder Wagon : Oklahoma City Fire Museum

The involvement of African-Americans in Columbia’s fire services can be traced back to the 1840’s. During the "volunteer days" as they were called, African-Americans worked for predominantly white fire companies and founded their own predominantly black fire companies. African-Americans who worked for white volunteer fire companies were hired as drivers. In the " volunteer days" the fire engines were horse drawn, and he men who drove them had to be able to handle a team of horses at very high speed. This was a difficult task, but African-Americans proved that they could handle the job. Their ability to handle horse-drawn fire engines made them popular throughout white and black communities.

In addition to driving the fire engines, African-Americans cared for the horses, cleaned the stables, and stoked the boilers of the steam pumpers. These were not glamorous jobs, but African-Americans performed them diligently. Despite having to perform these menial tasks, the African-Americans were still considered an important part of the volunteer fire company.

One of the things that helped bolster the popularity of African-American drivers during the "volunteer days" was their performance in the firemen’s tournaments. During the "volunteer days" fire departments from all around the state would come together to compete in firemen’s tournaments and to participate in parades. The tournaments helped the firemen keep their skills sharp. It also helped them stay busy when there were no fires to fight. Most of the tournaments consisted of a three day program of foot races, reel contests, and fire engine races. Many people attended the events, during the 1880’s firemen were more popular than baseball players.

Although African-Americans competed in predominantly white tournaments, no black companies were allowed to compete against white companies. The tournaments that black fire companies held were just as successful as the tournaments held by their white counterparts. Thousands of spectators came out to see them compete. The stands were filled with black and white spectators who cheered the great skills of the firemen. It was not an unfamiliar sight to see white and black faces in the crowd of an African-American competition. The tournaments provided a rare opportunity for black and white people to come together, free from the racial tensions of the time.

In the 1870’s, the city had two black companies, the Vigilant Fire Company and the Enterprise Fire Company. In the 1850’s, the Vigilant Fire Company had been a city sponsored unit with white officers and black firemen; eventually it became an all black fire company. The city had three predominantly white fire companies, the Phoenix Hook and Ladder Company, the Palmetto Fire Company and the Independent Fire Company. The Phoenix Hook and Ladder Fire Company was an all white fire company and no black men were allowed to join. Any black male could join the remaining companies. Slaves were also allowed to join these companies if they had permission from their masters.

The black fire companies served the city for more than thirty years. Black fire companies fought side by side with white fire companies. The black and white firemen got along well and they often shared in the liquor when a jug was passed around at a conflagration.

There was a good deal of cooperation between some of the white fire companies and the black fire companies. For example, during the late 1860’s the city was ravished by a series of fires. As a result, the white and black fire companies suffered damage to their fire equipment. At the time, the city was responsible for supplying the fire companies with fire equipment. Each fire company petitioned for more fire hose. After petitioning the city and getting no response, the Vigilant Fire Company, The Enterprise Fire Company and Independent Fire Company joined forces and wrote a joint petition to the mayor. The show of cooperation between the fire companies illustrated the camaraderie among firemen, despite their race.

During the "volunteer days" there were two major incidents that affected the relationship between black firemen and the community. The first incident took place in 1880. In the Fall of that year a parade was supposed to be held for the opening of the State Fair. The parade committee asked the white and black fire companies to participate in the parade. Rumors, however, spread that this was a trap designed to massacre African-Americans, as a result only thirty-three black firemen from the Vigilant Fire Company participated in the parade and no firemen from the Enterprise Fire Company participated. Fortunately no one was harmed and the parade was a success, but the incident planted seeds of distrust in the hearts of African-American firemen.

The biggest event that affected the relationship between African-American firemen and the city took place in 1892. On December 21, the Vigilant Fire Company and the Enterprise Fire Company rushed to the scene of a fire. As always, they performed above and beyond the call of duty. once the fire was extinguished, two of the African-American firemen entered the building to investigate the fire. Shortly after they had entered the building they were ordered to leave by a white police officer. They refused and were immediately arrested by the officer. the next morning they were fined ten dollars by the Mayor’s Court and released. On of the men arrested was John L. Simons. Simmons was president of the Vigilant Fire Company and a board member of the city’s fire masters. The fire masters were an executive board established by the city. They investigated fires and established fire codes. The board was composed of both white and black firemen, who worked for the local volunteer fire companies.

Simons believed that he had been treated unjustly. He argued that as a member the Board of Fire Masters he had the right to enter any building during the performance of his duties. In protest, he called an emergency meeting of the Vigilant Fire Company and the Enterprise Fire Company. At the meeting they agreed to relinquish their allegiance to the city of Columbia. In a letter published in The State, they wrote:

"Where as the action of the police Wednesday and the decision of the Mayor’s Court this morning indicated that the people of Columbia do not appreciate our efforts. Therefore, be it resolved that we the colored firemen, of the Vigilant and Enterprise Companies, do hereby withdraw or allegiance to the fire department of Columbia, S.C."

The Vigilant Fire Company and Enterprise Company never worked for the city again, despite this fact, African-Americans continued to drive fire engines for white fire companies.

In 1903 the city ended its contract with the volunteer fire departments and organized the first paid fire department. The new fire department was composed of the old volunteer fire companies. The paid fire department was divided into three companies. The Columbia number Three, The Independent Number One and the Phoenix Hook and Ladder Company.

Columbia’s paid fire department opened on February 1, 1903, under the direction of Chief William J. May When May became chief, he and many others requested that the city retain the services of the African-American drivers. The drivers were an important part of the fire department and their performance was critical to the success of the new department. The experience that the African-American drivers had could not be replaced. This made them the best men for the job. The African-Americans were hired and remained employed by the city until 1921, when all hose-drawn apparatus were discontinued.

Courtesy of Columbia SC fire museum

To commemorate the opening of the paid fire department a photo was taken of the Independent Number One. Present in the photo was Chief May, the Mayor and all the members.

[ Image missing ]

Photo courtesy of Columbia SC Fire Museum

Other cities used slaves in their fire departments some of them will be listed further on.

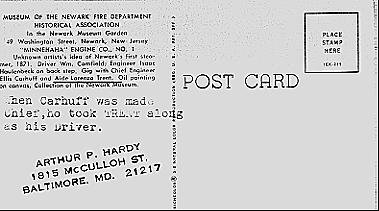

Post card from the collection of Arthur P." Smokestack" Hardy Inscription:

Museum of the Newark Fire Department Historical Association

"Minehaha" Engine Company No1

Unknown artist's idea of Newark's first steam pumper, 1871. Driver Wm. Camfield, Engineer Isaac Haulenbeckon back step. Gig with Chief Engineer Ellis Carhuff and Aide Lorenzo Trent.

Lorenso Trent shown on the far side of the chief engineer riding the other horse. A note by Arthur P. Hardy that when Carhuff made chief he took Trent as his Driver.

No history of Black Firefighters would be complete with out mention of one black man with a passion for black fire history. His story begins in Baltimore, Maryland almost 100 years ago. He was witness to the destruction of the Great Fire of Baltimore of 1903. He died December 3rd, 1995. His name was Arthur P. Hardy but he soon became “Smokestack” Hardy being named after the old smoking steam engines.

“Smokestack” lived his whole life dedicated to collecting historical information about black firefighters. He attempted to do with a manual typewriter and the US Postal Service what others are doing with computers and the internet. His collection grew each day as he corresponded with firefighters all over the world. He admonished all who desired to obtain information or collectable items to not belittle any response to your plea. Be diligent in replying to all correspondence. His contribution is invaluable.

If ever you are able to visit a museum with his “stuff” in it don’t pass it up. He was on top of every event in the fire service. He depended on his fire correspondents to “Ring In” keeping him posted. When he answered the letter he would always make reference to your ring of (m-d-y). His reputation did not skip notice of the media of the day. Ebony Magazine wrote him up on two occasions and local media did some feature atricles. Photos of his living quarters proved his ability to collect anything fire related. Reporters had a hard time finding a place to sit. He would collect anything related to fire.

Being an auxiliary firefighter with engine 13 of Baltimore and holding the title of Fire Photographer was the high point in his life. He held cards from fire departments far and wide allowing him to pass through the fire lines. He was Americas #1 black fire buff.

A private museum operated in the home of Guy Cephus displays a part of the collection of Smokestack Hardy. You should contact Guy Cephus at 410-462-3553 or write to 203 North Carey St. 1st floor, Baltimore MD. 21223. Guy will be happy to open up for you but you need to contact him first to be sure his is in.

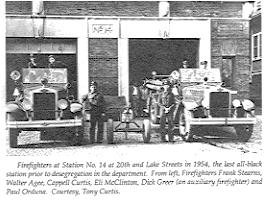

Given by Larry M. Scalise

In January of 1885, five black men were hired in the Omaha Fire Department to form Hose company #12. A few years later they moved to another station and designated hose company #11. Some of the early members of the Omaha black fire company were Capt. Joseph H. Henderson, Captain Scott Irving, Lieutenant Frank Johnson, Lieutenant E.W. Watts, Driver John Taylor, Pipmen Woodson Porter and Lewis Selby they remained segregated for sixty two years. They served the Department well even though for all these years they were isolated. The first change came in 1940 when one of the members was moved to the Bureau of Fire Prevention and Inspection. By the 50’s the number had grown enough to man two companies. In a photo taken in 1954 black firefighters were identified as Frank Stearns, Walter Agee, Cappell Curtis, Eli McClinton, Paul Orduna and auxiliary firefighter Dick Greer. Integration of the department came in 1957.

Photos copied from The History of the Omaha Fire Department

The migration of former slaves to Omaha was in a large part due to employment offered in the meat packing industry. Transportation up river from Mississippi and Louisiana was easy to come by work was exchanged for a ride on the river boats that plied the river.

Given by Dot and Bill Ketchum

"The first All-Negro fire-fighting Company was organized in Nashville on January 15, 1885. This All-Negro Unit was identified as Engine Company Number Four, and it was located on Woodland Street in East Nashville. C. C. Gowdy was the Captain of this company. His personnel was comprised of the following men: Aaron Cockrill, Lieutenant; Henry Driver, Engineer; James Trimble, Fireman; James Watkins, Pipeman; John Calhoun, Pipeman; Mose Hopkins, Pipeman; and John Harris, Pipeman.

"A third-class AHRENS Fire Engine was the equipment of Company Number Four: "The William Stock" was its name. Two horses names "Mark" and "Judge" pulled the engine. The hose cart was a four-wheeler. Two horses, "Buck" and "Morgan", pulled the hose cart. The hose cart reel carried 1,350 feet of two and one half inch hose.

"When Mechanized fire-fighting came into existence, Company Number Four was mechanized on March 24, 1920. The mechanization of Company Four marked the final company in Nashville to reach this stage. Company Number Four received a Pumper that had previously been used by Engine Company Number Ten.

"On January 2, 1892, when Weakley Warren Furniture Store was destroyed by fire, Captain C. C. Gowdy, Harvey Ewing, and Stanley Allen, members of Engine Company Four, were killed. The north wall of the furniture store feel onto the Phillips and Buttorff Company where they were standing directing a stream of water on the fire.

"On February 20, 1923, Company Four moved to 12th Avenue, North and Jefferson Street ("Goat Hill"), to replace Engine Company Eleven, which had been operating in the "R. O. Tucker" Hall. With the move from East Nashville to North Nashville, Company Four became Company Eleven. With the remodeling of the Company Eleven Hall in 1930, the name of the Fire Hall changed from the "R. O. Tucker" to the Reuben B. Richardson" Fire Hall.

"Ben Christian, a member of Engine Company Eleven, while rolling hose on 12th Avenue, North between Jo Johnston and Gay, was struck by a hit and run driver of a truck on January 17, 1939. He died January 31, 1939."

Information by Chris Clapp and Rev. Ron Ballew

What began in 1858 as an all volunteer fire department , with the usual buckets and ladders with cisterns for a water supply expanded to a paid fire department in the late 1800’s. Unlike a number of cities Danville had an all black fire company early on. Number Two Station at 705 N. Walnut St. was built in 1898 and was occupied from the first day by black fire fighters. There may have been black volunteers before this time but we have no record of them.

Engine house #2 as it now stands

A white firefighter named Sterling Ford who joined the department in 1946 recorded much of the history of the department and his comments about the black firefighters sums up the feeling in the community. "They were some of the best damn firefighters this city ever had."

Some but not all of those who served : Buford, John- Chavis, John- Cunningham, James- Day, Bud- Fletcher, Bill- Gaddie, Granville- Hunter, Morris- Kenner, C.N.- McDonald, E.H.- Miller, Marshall- Morris, Dallas Dudley- Nelson, Bill- Nichols, George R.- Norton, T.J.- Nosby, Jos. H.-Outlaw, Abe- Rosell, Dewey- Stuart, W.S.- Thompson, Henry- Wilson, Jos.P.

The earliest firefighters were not native to Danville but came from other states. Dallas Dudley Morris was born in Shelby, Alabama in 1878 was employed in 1905. Joseph P. Wilson was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi in 1873, employed in 1905. John Chavis was born in Chambersburg, Indiana in 1861, employed 1905. James a Cunningham was born in 1864 in Mansfield, Tennessee employed 1906. Cunningham had served as a police office prior to being firefighter. His previous experience suited him for a leadership roll and he served as Captain for a number of years.

These men took on a special roll in the community. Children from the neighborhood knew that they were welcome at the fire station and the men took on the roll of councilor. The door was always open and a friendly face was there to greet them. A pool table, horse shoes and trapeze were available to them. A hungry child knew where to get a meal and get his face washed or get his shoe repaired. They took in the whole neighborhood when there was a need. Black children and white children felt the same welcome and even on the days when they were off duty a fishing lesson on how to catch crapie and blue gill was in order. A special bond was created between the children and the firemen and a wave of recognition from one of them as they sped to a fire was source of pride.

The children would sit wide eyed as the firemen talked about some of the fires they had fought. The story of one fire was told and retold and each time with the same fascination as before. February 17, 1915 a fire at the Woodbury Book Store, Will Stuart and Clarence Kenner were working the fire 54 feet up on a ladder when the wall collapsed killing two fire fighters and breaking Stuarts arm. Kenner was thrown from the ladder and landed inside of the walls. He was not seriously hurt in the fall but was unable to free himself, fellow firefighters played hose lines around him to keep the fire away but the thing that sustained him throughout the ordeal was a picture of Jesus that had fallen to lean against the wall at his feet. That picture was the inspiration that made him know that he would survive.

[ Image missing ]

In the early years politics played a big part in who got a job and who kept a job. There was no resentment in being segregated when the department was formed for they all knew that if an opening came at number two for a job it would go to a black man. With politics what it was no one would get the job that they didn’t want.

The firemen of number two took pride in their station and its equipment. Shining brass and white washing the curb. Scrubbing floors until they shined. The uniforms were just as important. They were accomplished cooks and the meals they prepared were shared with many of the neighborhood children.

The district they served included the mercantile area and they responded to most of the major fires. It also included residence of both poor and rich. When a fire occurred in the more affluent neighborhoods they wanted the men from number two to respond as they had much confidence in their ability.

Integration came to the department in 1963 and the station that had been a neighborhood focal point was closed when a new station was built to replace it. The station was replaced but the memories of those who served and those who were served has not gone away. The full impact on the lives of the young children both black and white that saw the men that worked here as their heroes and roll models will never be known.

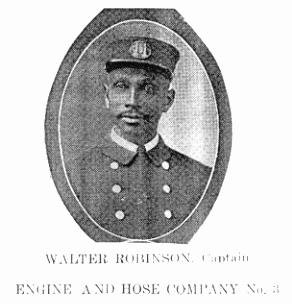

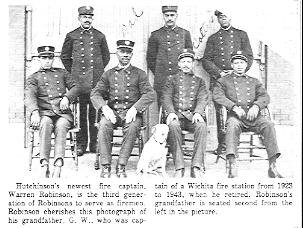

Information from Warren Robinson

![[Image]](images2/image024.jpg)

A study of American History helps us to understand how the settlement of the colonies was undertaken. The move westward began slowly but always there was a push to move farther west. The Mississippi River had slowed the westward movement until the United States Government made a decision to move the five civilized tribes to land in what is now Oklahoma. The tribes were the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek and Seminole. These tribes had developed an advanced system of government, law enforcement and education of their people. The move began in 1820 with the last tribe being moved in 1842. Many of the Indians were slave owners and as such took their slaves with them. This is how a number of early black residents made the move.

During the war between the states large numbers of the dislocated Indians chose to fight for the South. The Indians had been promised territory of their own. Each tribe had been assigned a large tract of land and they were designated as Nations. After the war three things occurred that encouraged the movement of blacks to the new frontier.

First when Oklahoma became a state in 1907, in retribution for the Indians alliance with the South the Federal Government chose to eliminate the Indian Nations. Each Indian was allotted a parcel of land. There was also a large area of land in Oklahoma Territory known as unassigned land. In an earlier agreement with the Cherokee Indians a strip of land across Oklahoma below the border with Kansas was given as a passage way to the hunting grounds of the west. Pressure grew for the opening to settlement of all of these lands.

Second the emancipation gave the blacks a right to vote and they were encouraged to start new businesses and to settle on land offered by the Federal Government. Fliers were distributed across the South extolling the virtues of living in the new territories. Kansas was considered the promised land. At one time the State of Oklahoma was being considered for an all black state.

The third event was the demand for beef in the east. During the War Between the States the number of Buffalo declined and the number of Longhorn Cattle increased. The Longhorn had become wild and all that was needed to claim these cattle was to catch them and brand them then deliver them to market. These cattle were captured from all over what would later be the State of Texas and driven to rail heads for shipment to the east. One such location for the shipment of cattle was Abilene, Kansas. The drovers that herded these cattle had a long and dangerous trip to make. The Indians, Jayhawkers and natural events such as storms and floods claimed the lives of many a young cowboy. Most of these young men were in their teens and it was not difficult to sign on with one of the cattle companies. After such a journey many decided this was not the life for them and they chose to settle in one of the towns along the way. For a newly emancipated slave this could be a quick way to see what life was like in other parts and find a job. Wichita, Kansas was an attractive little town along the route.

The end result was that 27 all black towns were established in Oklahoma and as many in Kansas. Though few of them still survive. They failed because of economics. The depression of 1929 hit hard in this area and not only black communities but white communities failed as well.

[ Image Missing ]

Richard and Sarah Robinson moved to Wichita, Kansas just prior to the 1870’s with them their two sons George Walter and Samuel James, they were the only black family in Wichita at this time. It is said that when they first arrived they shared a house with 5 white men from Pennsylvania, the Robinsons having come from Pennsylvania as well. The children were able to watch the town of fourteen houses grow into a city. In mid-1870’s a petition to make Wichita a town was delivered to Judge Reuben Riggs asking to incorporate. The petition had 123 signatures, one of which was Richard Robinson the only black person to sign. On the same document was the signature of only one woman. Catherine McCarty, who was to become the mother of "Billy the Kid". As the town grew and the children grew to be young men the town needed fire protection.

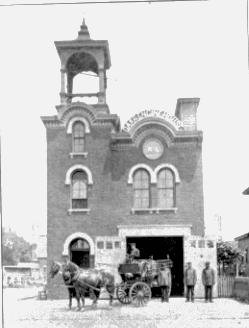

George Walter Robinson joined the Wichita fire department on November the 17, 1896 he was later promoted to Captain and served for 43 years. Fire Station #3 Engine and hose company was manned by an all black fire company. Some of the firefighters that served with him are Syl Anderson, William Whitted, C. A. Glover, Frank Hill and W. H. Jones. George Had a son named Gerald who also joined the Wichita Fire Department seven years after his father retired. Gerald had a son name Jess Warren Robinson who joined the Hutchinson, Kansas Fire Department seven years before his father retired and served until his retirement in 1996 as a captain. For 100 years a member of the Robinson family was in the fire service of Kansas. Warrens mother had a brother that also served in the Wichita Fire Department

by Rodney K. Smith and Arthur F. Rankin

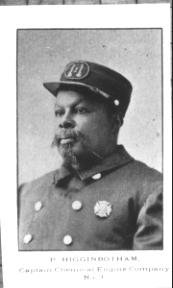

Capt. P. Higginbotham, Chemical Engine Company No1

Early records of Black firefighters in the Columbus Fire Department are limited. Historical records indicate that perhaps the first Black firefighters entered the fire department some time after the Civil War. Firefighters P. Higginsbothom and J.M. Logan are believed to have been the first Black firefighters in Columbus.

By 1892, P. Higginsbotham, then the oldest firefighter in the service of the department, was Captain of Chemical Engine Company No. 1. This station was located at Oak Street and Marble Alley which was the Old 12 House. J.M. Logan was Lieutenant at the same fire station. History records indicate that this firehouse was manned by the "Colored Contingent." In 1892 two additional Black firefighters entered the fire department and were stationed at the Oak Street firehouse. These men were R.C. Smith and Jesse G. Payne.

Family records reveal that during his history years of service with the fire department Payne, never received a mark against his record. He attained the rank of Captain before he retired on January 1, 1931.

The waning years of the 1920’s and early 1930’s saw the end of a period in the history of blacks in the Columbus Fire Department. Almost immediately though, like a Phoenix rising from the ashes, there emerged a new group of young men selected from a Civil Service eligibility list to undergo a thirty day period of concentrated and strictly-disciplined training in fire department procedures.

Thus in the summer of 1935 a new era begun. Installed in No. 8 Fire Station on North Twentieth Street were sixteen Black firefighter assigned to Pump Co. 8 and Truck Co. 5. Of these men, A. Green, J. Costen, W. Brown, V. Green W. Huckleby and J. Jones were promoted to Lieutenant, C. Alston and C. Johnson became Captains, w. Boyer and C. Jones became Battalion Chiefs and Herman Harrison became Deputy Chief, second in command only to the Chief of the department.

After sixteen Black firefighters entered the department in 1935, the following ten year period between 1937 and 1947, saw six additional men join their brothers. In 1948, eight additional firefighters entered the fire department. This brought the total number to twenty-eight, the highest number at any one time in the history of the department.

When the next group entered the department in February of 1954, a significant change took place. Fire Station No. 8 that had been previously occupied by all black, became desegregated.

Within the next eighteen year span, between 1955 and 1973, twelve additional firefighters joined the ranks. By the fall of 1973, the number of firefighters had dwindled to eighteen. In November of that year, litigation was initiated seeking redress under Title Seven of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1975, the courts ruled in favor of he plaintiffs and thereafter, the City of Columbus developed a strong affirmative action program.

In April of 1980, Columbus’ first female firefighter entered the recruit training class. Diana Rissell graduated from the training academy in August 1980 and was assigned to Station No. 2.

In March of 1989 the African American firefighters began holding informal meetings to discuss the trials and tribulations that they were experiencing. They formed an organization and it was incorporated with the State in November of the same year. This organization is call the Columbus African American Firefighters Association. The organization motto is "African by Nature-American by Experience."