Memories of the Mangel’s Building Fire – July 7, 1981

Note: This documents is best viewed in PDF format. See

http://www.raleighfiremuseum.org/content/mangel

Memories of the Mangel’s Building Fire – July 7, 1981

Note: This documents is best viewed in PDF format. See

http://www.raleighfiremuseum.org/content/mangel

This document was created by Mike Legeros. This is version 1.1, last updated on August 1, 2016.

Thanks to the many contributors, including William Artis, Donnie Carter, Creighton Edwards, James Farantatos, Wayland Holden, Gary Knight, Al Moore, William Ott, Danny Poole, Cindy Rubens, Donald Summers, and Randy Wall.

Let’s travel back in time to the early Eighties, to the second year of that decade. The summer of 1981. Ronald Reagan is President, and has survived an assassination attempt. Pope John Paul II is also recovering from gunshot wounds. The Oakland Raiders are the year’s Super Bowl champs. Major League Baseball has gone on strike. The Centers for Disease Control have identified the first recognized cases of an acquired immunity deficiency disease.

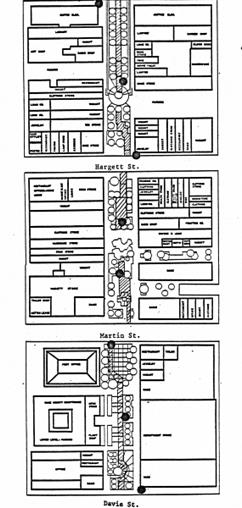

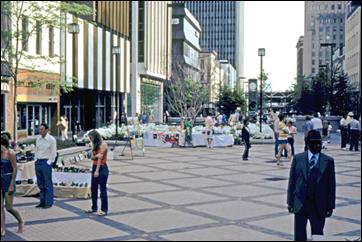

The City of Raleigh is less than half its present size at 56.63 square miles, and its population is less than a third of its present amount at 149,771. It’s the state’s third largest city. G. Smeades York is serving his second term as Mayor. The Fayetteville Street pedestrian mall and the Raleigh Civic Center are four years old. The merged Raleigh and Wake County school system is five years old.

The Raleigh Fire Department has fifteen fire stations, with sixteen engines, three aerial ladders, three service ladders, two rescue units, and three District Chiefs.[1] They’ll answer 5,214 calls in 1981. This is also the second year of the city-wide first responder program. They have 325 authorized positions (with 299 in Operations), and a budget of $5.7 million. The Fire Chief is Rufus Keith. The Assistant Chiefs are Norman Walker (Operations) and C. T. May (Services).

The month is July, the day is the seventh. Tuesday, July 7, 1981. The forecast says sunny, with warmer temperatures and high humidity. The weather station at the airport will record a high of 90 degrees that day, with a dew point of 73 degrees, and a maximum humidity of 93. No precipitation, and wind speeds of 5 mph, with maximum gusts of 9 mph.[2]

At about 8:45 a.m., the attendant in a parking lot in the

100 block of S. Salisbury Street noticed smoke coming from the Mangel’s

Building next door. He saw smoke coming from a second-floor window. He went

inside, into the Corkscrew Restaurant, and informed the owner of what he saw.[3] The owner

called the fire department and Engine 1 and Engine 3 were dispatched at 8:50

a.m. to a smoke investigation.

At about 8:45 a.m., the attendant in a parking lot in the

100 block of S. Salisbury Street noticed smoke coming from the Mangel’s

Building next door. He saw smoke coming from a second-floor window. He went

inside, into the Corkscrew Restaurant, and informed the owner of what he saw.[3] The owner

called the fire department and Engine 1 and Engine 3 were dispatched at 8:50

a.m. to a smoke investigation.

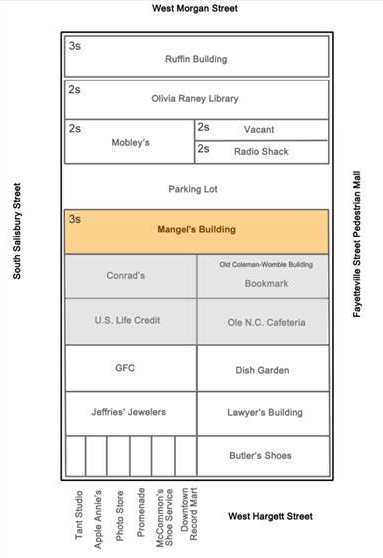

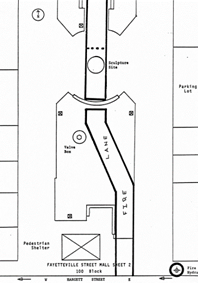

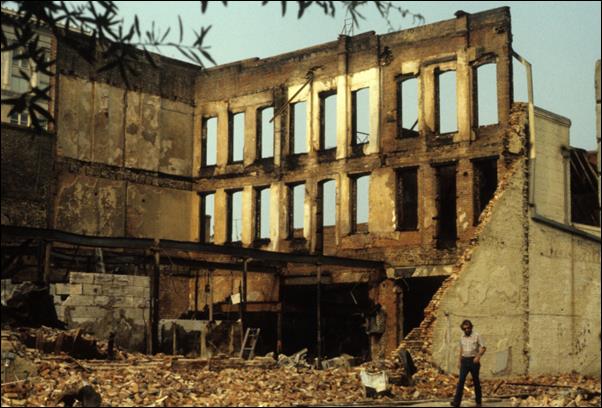

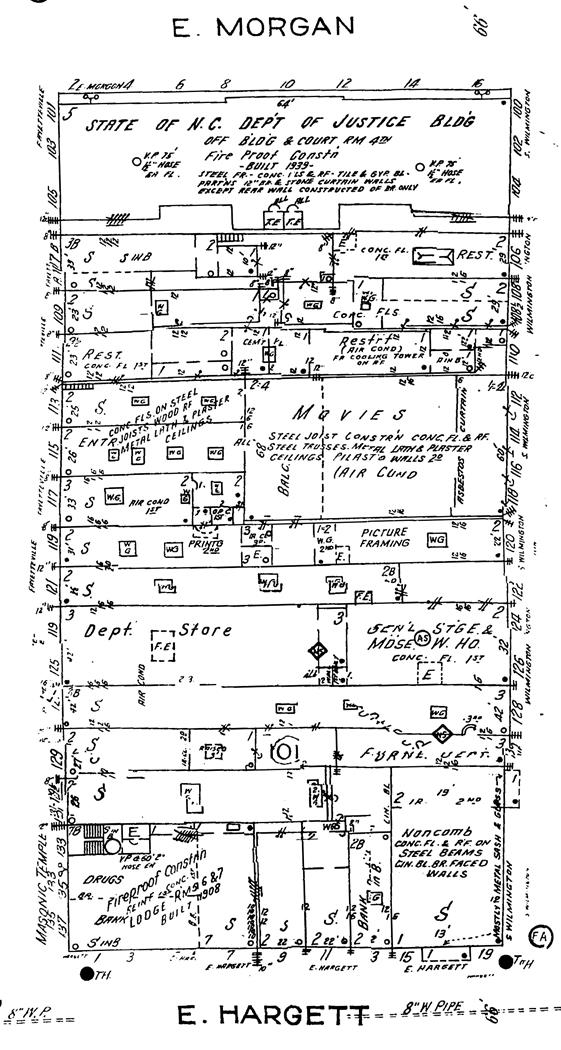

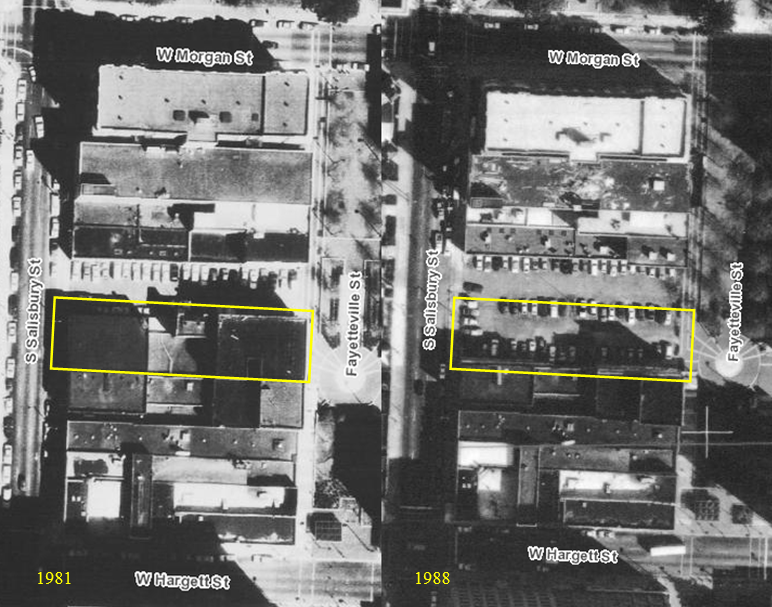

The Mangel’s Building was a three-story, eighty year-old building at 124 Fayetteville Street Mall, in the middle of a block bounded by Morgan, Salisbury, and Hargett streets.[4] It spanned the width of the block, with a front entrance on the mall and a rear entrance on Salisbury Street. The first floor was divided into two main businesses—the Corkscrew Restaurant and the Raleigh Bazaar flea market—and ten smaller ones.[5] The second and presumably third floor were empty, neither occupied, nor used for storage. The building adjoined two others on its north side. There was a small parking lot on its south side.

Built between 1890 and 1900, the Mangel’s Building had a masonry exterior that covered solid wooden construction: timber beams and columns, and hard pine floors. Over those were plaster and sheetrock ceilings and walls. It had also been extensively remodeled inside, with what fire officials would later call a “labyrinth of subdivided rooms and false ceilings.”[6] The total square footage was 24,940 square-feet. The building bore the name of a longtime woman’s clothing store that was located there until 1975.[7]

There was no sprinkler system, but it was equipped with a pair of portable fire extinguishers.

Raleigh

City Directory, 1960

Raleigh

City Directory, 1960

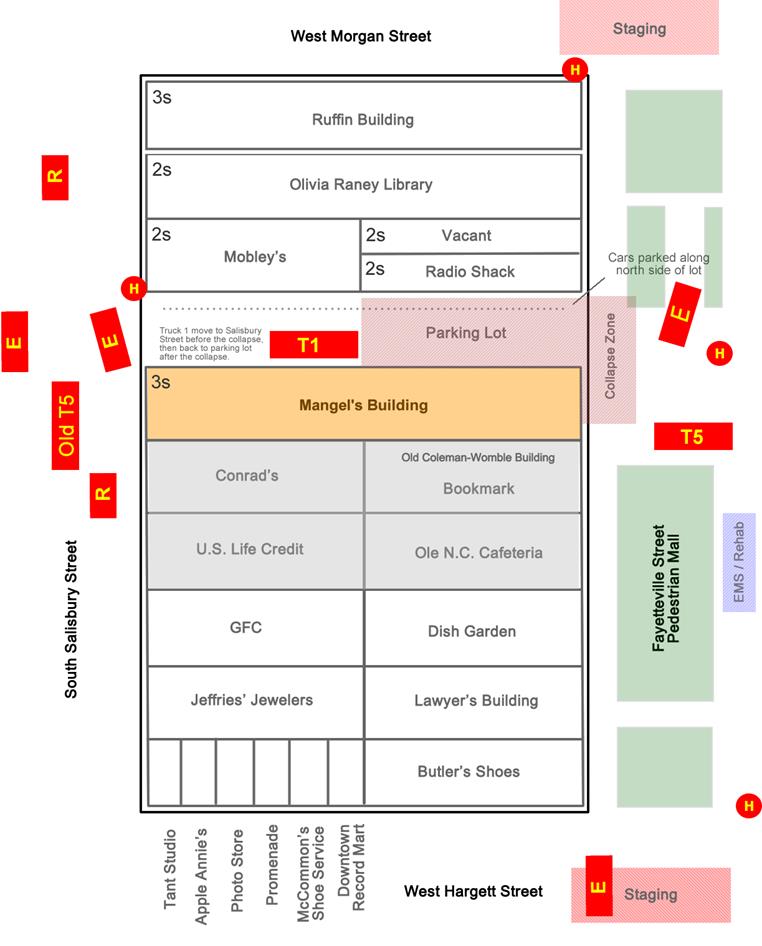

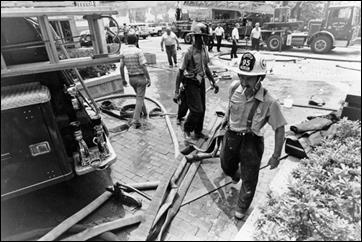

Engine 1 arrived at 8:54 a.m. and just ahead of Engine 3. They parked on Salisbury Street, and found light smoke conditions inside. As they began investigating—with two firefighters going inside with a hose line—the smoke, and soon, heat increased. Conditions quickly worsened, and heavy smoke started showing along with high heat. Engine 1 hooked to a hydrant beside the building, while Engine 3 moved onto the mall, and connected to a second hydrant. Truck 1 was requested, and was followed by the dispatch of three additional engines and a second truck company between 9:04 a.m. and 9:15 a.m.

Thirty minutes later, Rescue 12 was dispatched at 9:39 a.m. and a third aerial ladder, Old Truck 5, was brought from Station 15 at 9:45 a.m. No formal first- or second-alarm assignments were apparently dispatched.

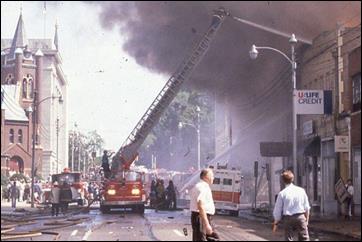

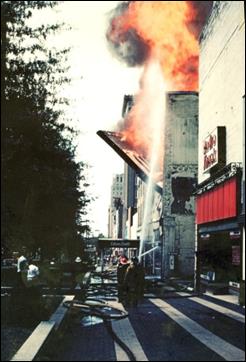

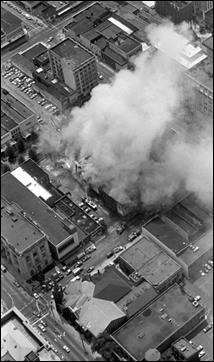

By the second hour, flames were showing from the roof. Smoke billowed from the structure and filled the pedestrian mall. Firefighters pressed onward inside the building, trying to find the seat of the fire. More companies were dispatched: new Engine 13 at 10:15 a.m., Rescue 14 at 10:26 a.m., reserve Engine 2 at 10:30 a.m., and Engine 13 at 10:44 a.m.

New Engine 13 was a recently delivered Mack pumper parked at Station 2 and not yet in service. It was called to the scene, along with eighteen firefighter recruits in class at the fire station.

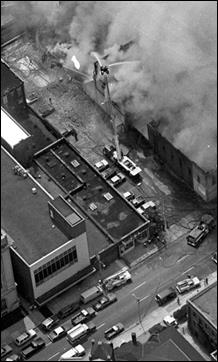

By the third hour, bulges and cracks in the building’s walls were observed. Floors inside the building had already collapsed. Firefighters were no longer inside the structure—due to the danger—but were still standing in doorways, training their hose streams into the building. Other firefighters manned portable monitors on the mall and in the parking lot.

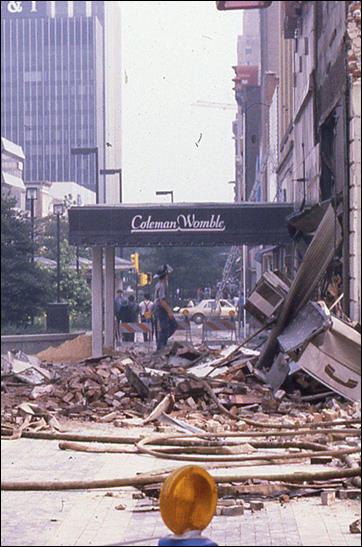

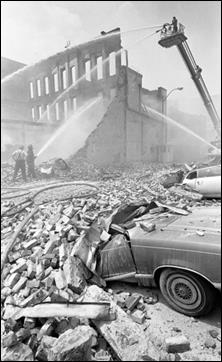

About 11:00 a.m., the walls on two sides of the building collapsed and showered debris into the mall and the parking lot. Crews abandoned their hose lines and portable monitors. They scrambled from the falling debris and escaped injury.

The collapse was helpful to the firefighters, as it helped relieve the heat and pressure inside the burning building. Firefighters picked through the rubble, to find their hoses and nozzles, and resumed spraying water on the fire. Truck 1 was also moved back into the parking lot, and continued its aerial streams.

The equivalent of a third alarm was dispatched around 11:30 a.m., with Engine 11 at 11:28 a.m., Engine 9 around the same time, and Engine 6 at 11:45 a.m. The equivalent of a fourth alarm was dispatched just after noon, with Engine 10 at 12:01 p.m., both Engine 7 and Truck 7 at 12:02 p.m., and Engine 8 at about the same time.

By noon, the fire was under control. Additional engine and truck companies continued to be sent to the scene through the day, including Truck 16, Engine 15, and Engine 14. Other companies left and returned, such as Truck 1 which was re-dispatched at 2:33 p.m., and Engine 7, which was re-dispatched at 5:18 p.m. Crews would remain at the scene of the fire through at least Thursday.

The Mangel’s Building fire started in the back of the building, in a small area between the first and second floors. The building’s wooden floors and false ceilings helped fuel the fire, which quickly mushroomed and spread through the rest of the structure. Flames leap thirty feet into the air after the fire vented through the roof. The wind was in the fire department’s favor, however. There was only a slight breeze, and though originally blowing toward the exposures next door, it later reversed.

Crews had difficulty both finding and controlling the fire,

as the first floor of the building was heavily portioned. “It was like fighting

five separate fires at once” said District Chief Lewis V. Choplin in later news

stories.[8]

The structure had numerous false walls and ceilings added as the result of

renovation work over the years. “You name it, they had done it in there,” added

Fire Chief Rufus Keith. “We couldn’t find [the fire]. We never really found

[it].”[9]

Crews had difficulty both finding and controlling the fire,

as the first floor of the building was heavily portioned. “It was like fighting

five separate fires at once” said District Chief Lewis V. Choplin in later news

stories.[8]

The structure had numerous false walls and ceilings added as the result of

renovation work over the years. “You name it, they had done it in there,” added

Fire Chief Rufus Keith. “We couldn’t find [the fire]. We never really found

[it].”[9]

The intensity of the blaze grew as each hour passed. The owner of the Bookmark was planning to open at 10:00 a.m., but the building next door—that shared a common wall—was blazing. And “it seemed to get worse and worse,” he recalled to reporters. “The more firemen that came, the worse the fire got.”[10] By 11:00 a.m., the owner was forced to abandon his shop, and taking memorabilia and some books with him.

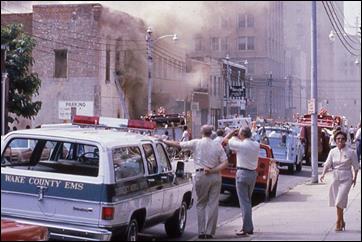

Black smoke covered the Fayetteville Street Mall like a blanket, and shoppers found fresh air inside stores farthest from the fire. Those businesses closer to the Mangel’s Building were impacted by smoke and water damage, as well as power and phone outages. The fire also attracted hundreds of spectators to the scene, with crowds so large that the police department sent special teams to watch for pickpockets and looters.[11]

In addition to the many hand hose lines and portable ground monitors, three pieces of aerial apparatus were used to spray water into the upper stories of the building and onto the roof:

·

Truck 1 - 1977 Mack/Baker 85-foot aerial platform.

Parking lot beside the building, then temporarily moved to Salisbury Street.

·

Truck 5 - 1979 Mack/1958 American LaFrance 100-foot aerial

ladder.

Fayetteville Street Mall, facing the front of the building.

·

Truck 5, Old - 1961 American LaFrance 100-foot aerial ladder.

South Salisbury Street, parallel to the back of the building.

At

about 11:00 a.m., the walls collapsed. First, a section on the mall side sent

firefighters scrambling, and then a second section crumbled into the parking

lot.

At

about 11:00 a.m., the walls collapsed. First, a section on the mall side sent

firefighters scrambling, and then a second section crumbled into the parking

lot.

The collapse was expected. Cracks and bulges in the walls had been observed and were being watched closely by the chief officers. Truck 1 was moved from its position in the parking lot to a safer spot on Salisbury Street. And firefighters with hand lines were not allowed inside.

Then a section of the wall on the mall side began peeling away. [12] The crews ran for cover, leaving their hoses in place. It was a close call for some, as one firefighter remembered bricks striking the back of her boots as she ran from her abandoned hose line. After the first collapse, a section of the south wall collapsed into the parking lot. The falling rubble crushed two cars and damaged a third. [13] No one was injured, however, on either side of the building.

Noted the news stories, “a collective gasp rose from spectators” who were watching the blaze. As the wall tumbled, they felt a “blast of intense heat.” Recalled Raleigh lawyer Thomas C. Manning, “It was just like a wave of heat rolling down that mall.” He added, “It was like opening an oven when you’ve got a turkey cooking. That’s the way it felt.”[14]

“It was a blessing,” Chief Keith later told reporters, “because it relieved some of the pressure [inside the structure].”[15] Had the wall not collapsed, he speculated, fire might have spread to the roof of the vacant Coleman-Womble building next door. Fire did creep into an elevator shaft leading to the building, but damage was minimal due to the Mangel’s Building’s fire wall.[16]

“We knew we had lost [the building],” said Chief Keith, “So we had to concentrate on keeping it from jumping the rooftop and spreading to [next door].”[17] The parking lot on the south side also acted as a fire break and prevented the fire from spreading to the buildings on the north side of the block.

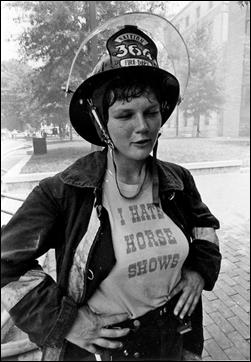

More than 100 firefighters responded to the fire, including off-duty members and firefighters from suburban volunteer fire departments. [18] Also helping were nineteen recruits from the fire academy, due to graduate on July 17. They fought the fire for over three hours in temperatures ranging between 83 and 89 degrees.

Every fire station in the city sent units to the scene, either as part of the original response(s) or as special called units or relief companies. Those companies still in service concentrated on coverage in the downtown area, while Cary, Garner, and Six Forks fire departments provided coverage in other areas of the city.

Over thirty firefighters suffered smoke inhalation and heat exhaustion, and were treated by Wake County EMS personnel and the two fire department rescue squads. Eleven or twelve were transported and treated at hospitals, while more than twenty were treated at the scene. Firefighters sprawled upon the grassy areas of the mall, “sucking oxygen and gulping down soft drinks and water,” as the News & Observer wrote. [19] Salt tablets were also distributed, after officials purchased all eight bottles on the shelves at the nearby Revco drug store. No serious injuries were reported.

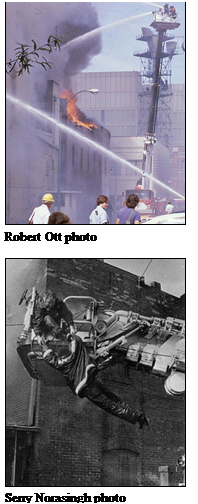

One

dramatic moment was caught on film by Raleigh Times photographer Seny

Norasingh. He captured firefighter Reggie Perry clinging to the outside of the

bucket of Truck 1. Or what was called in some news reports as the fire

department’s “cherry picker.”

One

dramatic moment was caught on film by Raleigh Times photographer Seny

Norasingh. He captured firefighter Reggie Perry clinging to the outside of the

bucket of Truck 1. Or what was called in some news reports as the fire

department’s “cherry picker.”

As the story goes, the platform was raised with two firefighters in the bucket when flames exploded from the roof. Perry instinctively jumped, but was grabbed by Thomas “T.J.” Lester before he could fall. As the tower was rotated and then lowered, recounted the Times, the unmanned master stream sprayed in an arc that sent spectators on the mall scrambling for shelter.

Norasingh's photo was transmitted on national news wires, and the picture appeared in newspapers across the country. The city subsequently received notes from other fire departments that saw it. The photograph became well-known within the fire department, though the details of the rescue have been less well-preserved.

Some tell the story as heavy smoke sending Perry out of the bucket, while others say it was fire. The truth is a combination of both.

Prior to the wall collapse, Truck 1 was still operating from the parking lot beside the Mangel’s Building. Two firefighters had already been in the bucket, and were sent to the hospital with smoke inhalation. They were replaced by Perry and Lester.

While airborne and over the fire, nearby refrigerant lines ruptured on an air conditioning unit. The escaping Freon gas became heated, and produced Phosgene gas. The effects of this acrid and deadly gas—most famously used as chemical warfare in World War I— were felt by the men in the bucket. But as they attempted to move the bucket using their controls, the controls didn't respond. At the turntable, the driver/operator had inadvertently depressed a pedal that overrode the controls in the bucket.

The effects of the gas compelled Perry to jump. He was caught by Lester, and both were caught on camera. The bucket was lowered, the truck was moved before the wall collapsed, and both the photo and the fire became a part of history.[20]

Hundreds of spectators lined the mall and Salisbury Street. Some could feel the heat even a block away on the Salisbury Street side. Dozens of police officers responded, to secure the area and control the crowd. They roped off the area, and the immense crowd was orderly. Members of the police department’s Selective Enforcement Unit also responded and watched for pickpockets and looters. No vandalism or larceny was reported.

Buildings were evacuated for several hours in the 100 block of the mall, as well as some in the 200 block. Many of the spectators were employees from the emptied buildings. Judges of the state Supreme Court and Court of Appeals watched the blaze, along with attorneys whose offices were on the mall.

At the Lawyer’s Building at 134 Fayetteville Street Mall, two attorneys called two moving vans to the Hargett Street corner of the mall, after firefighters told them that they had about twenty minutes to vacate their offices. “We formed an assembly line and moved everything out but the furniture,” said lawyer Thomas C. Manning.[21]

Traffic in a two-square block area was diverted during the incident. Electric power to the entire block was shut down, and telephone service was also disrupted to a number of stores as a cable on the Mangel’s Building melted. Twelve businesses lost power, and at least eight lost phone service.

This was also the first major fire on the Fayetteville Street Mall, which had been converted to a pedestrian mall a few years earlier.

It was described as “one of the largest fires in the downtown in recent years” by Jerry Heath, Assistant Director of the Raleigh-Wake Communications Center.[22] “As far as involvement and handling,” added Chief Keith,” this is the worst in about ten or twelve years.”[23] He also said the incident used more personnel and apparatus than any fire in the city’s history.

The Mangel’s Building was occupied on the first floor only, by two main businesses and ten smaller ones:[24]

|

|

Name |

Owner |

|

Main |

Corkscrew Restaurant |

Henry Mouchahoir |

|

Raleigh Bazaar |

Ann Jensen |

|

|

Smaller Businesses |

Allreds Home Fashion |

Ann Allreds |

|

Devone’s Fashions |

Raymond Devone |

|

|

Discount For Beauty |

Jim & Deloris Lawrence |

|

|

Gems & Silver |

Ralph Warner |

|

|

Invention Marketing |

Chuck Atkinson |

|

|

Second Story Books |

Carrol Sugg |

|

|

This & That Brass Items |

Blair Smith |

|

|

Victoria Limited – Antique store |

Ann Jensen |

|

|

Concession stand |

Zel Warner |

|

|

Unnamed |

Betty Sager |

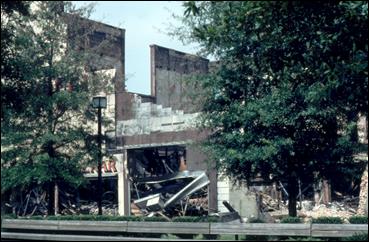

All of the businesses were destroyed, and the building itself was a total loss. The tax value according to county records was $63,190. Its value and corresponding damage was recorded by the fire department as $229,750.

The Mangel’s Building was insured for $150,000. The Raleigh Bazaar was not insured, nor were the tenants. They were unable to purchase reasonably priced insurance, said the Bazaar’s owner to the News & Observer, because of the building’s age.

The Corkscrew Restaurant had $18,429 of property, $20,000 of insurance, and $80,000 of damage. The value of the Raleigh Bazaar’s inventory was estimated at $150,000 to $175,000. [25] Damage to the Bazaar was estimated as $10,000.

Damages to the smaller businesses as recorded by the fire department were:

· $8,800 - Allreds Home Fashion · $7,000 - Discount For Beauty · $5,000 - Invention Marketing |

· $4,000 - This & That Brass Items · $3,000 - Concession stand · $2,500 - Devone’s Fashions · $2,000 - Betty Sager’s business · $950 - Second Story Books |

Total damage was $229,750 for the building and $188,250 for the contents.

Many businesses along the 100 block of the Fayetteville Street Mall suffered smoke damage. Most of the establishments reopened the next day. At the Bookmark, the manager didn’t see much damage to the bookstore. “I’ll just blow out the smoke,” he said. [26] Little damage was found at the Ole N.C. Cafeteria, which was open the next day.

Olivia Raney Library at the end of the block was also open, and with no smoke or water damage. Only the smell of smoke was present, said a librarian. They were helped by the wind, which was blowing away from the library on the day of the fire. U.S. Credit Life was open but with minor smoke damage. Radio Shack was closed, due to lack of either electricity or telephone service. Little damage was reported at the store, though the manager’s 1971 Chevrolet Impala was destroyed by the wall that collapsed into the parking lot.

Stores closed due to damage included Conrad’s Uniform, which suffered smoke and water damage amounting to about $20,000. The Dish Garden also suffered smoke damage, and the owner hoped to reopen in a few days.

Other businesses were impacted on the day of the fire because they had to close after evacuating.

Brittain’s department store had recorded just a single sale—one dress for $35.36—before police evacuated them, just minutes after the wall collapsed across the mall. Some stores closed due to loss of power, and in turn suffered losses from spoiled food and dying plants during the outage. The longest break in power was four hours. The interruption of phone service continued into the day after, for about a dozen small businesses on Salisbury and Hargett streets.

The impact on mall businesses varied considerably and was based on their distance to the fire. At Hudson Belk, near the south end, manager W. J. Hudson said “it’s just been a normal day.”[27]

Some businesses benefited from the fire and the spectators it attracted downtown. Crowds flooded Hardee’s on the mall. The fast-foot restaurant reported sales $500 above normal by 5:00 p.m. Sales also jumped 50 percent at Sunrise Biscuit Kitchen on Wilmington Street. They likely drew patrons that would have otherwise visited the restaurants that were closed due to the fire.

By 1:00 p.m. the next day, most of the businesses closed due to smoke and water damage had reopened.

Who were the recruits sent to the fire scene that day? The Class of 1981 (later named Recruit Academy 6) graduated the following members two weeks later. All but Greg Wall, currently a captain, have retired (ret.) or resigned:

Speculation began immediately on the cause of the blaze. The manager of the Raleigh Bazaar said that the business had been having trouble with the air-conditioning system for two weeks. Fire Inspector Wayne Robertson also said that the store’s opening several months ago was delayed due to fire code violations. However, all regulations were in compliance before the store opened.[28]

By the second day, the origin of the fire had been determined. The fire started inside Victoria Ltd., a small antique shop that was located in the rear of the first-floor flea market. The owner of the store, who also managed the Raleigh Bazaar flea market, said the shop’s air-conditioning system had been having problems.

Attention was also drawn to the “tinderbox nature” of other old downtown buildings. “It was a building designed to burn up after it catches fire,” Chief Keith said. [29] Almost half of the forty-six buildings along the Fayetteville Street Mall were similar to the Mangel’s Building, said fire and insurance officials. These were older wood-joist and masonry buildings, most of which were built with “heart pine.”

That was considered “premium grade timber,” said James E. Briggs, former Mayor and owner of Briggs Hardware on the mall. “That kind of lumber is full of sap, even after all these years,” he told the Raleigh Times. “It still contains all those chemicals, all that turpentine. Most of the floors in these old buildings have been treated with oil. We used something much like motor oil. All very combustible. We’ve probably got the most combusting [building] there is [on the mall].”[30]

The same officials noted that though the older wood-frame buildings were no more prone to fires than newer buildings built of less combustible materials, they were nearly impossible to control once a fire started in them. “There is always the possibility of conflagration, of the entire block going up,” said Assistant Chief and Fire Marshall James T. Owens.[31]

Renovations to the building also hampered the efforts of firefighters, who encountered a maze of subdivided rooms with partitions and false ceilings. Noted Chief Keith, “We couldn’t find the fire to ventilate it [and relieve the built-heat and pressure].” He added that many of the renovated buildings downtown had such mazes. They were considered fire safe, but were still a barrier to firefighting. “They’re restoring a lot of the older buildings, and it’s great for historic preservation, but not for us,” he said.[32]

For all of its partitions, the Mangel’s Building did not violate the fire code, said Chief Owens. But other buildings could be in violation. Construction Inspector Supervisor Gene Harrison told the Raleigh Times “There’s no way we can go through all of them. We don’t have the manpower. I would not be surprised to see that work has been done unbeknownst to us that doesn’t comply, I’m sure it does pose a problem.”[33] He noted that store owners who install false ceilings and walls must use materials that can contain a fire for one hour.

City building inspector Bobby Brown told the News & Observer that the first floor of the Mangel’s Building complied with the “minimum standards” of the North Carolina Building Code, but the second floor would not. The upper story was exempt from meeting those standards, however, since it wasn’t occupied as a business nor used as storage.[34] Nor was a sprinkler system required. For older buildings like the Mangel’s Building, the state building code required only a fire extinguisher and a plan to evacuate occupants in the case of fire.

Investigators determined within days that a faulty fluorescent light fixture located in a false ceiling above the first floor apparently ignited the wooden ceiling above it. “The fire was just rolling [inside the false ceiling] and it could have been burning from Salisbury Street to the mall street side [by the time firefighters arrived],” said Chief Keith[35].

Fire officials, police detectives, and engineers had combed the remains of the building. They agreed that the fixture’s transformer or ballast apparently shorted and began heating up the nearby wooden ceiling and support structures. The fixture was located in the rear of the building’s north end.

The investigators identified that area as the fire’s origin, which was directly below a pair of floor air-conditioning units on the second floor, in the north side of the building nearest to the Salisbury Street entrance. They first thought the air-conditioning units may have caused the fire. No problems were found after the units were lifted from the rubble using a crane, and subsequently studied by engineers.

Chief Owens said that the investigators turned to the rear of the building’s north end because of burn patterns found there, and reports from witnesses who saw heavy smoke from a window near that side of the building.

Investigators examined other electrical components in the area, said Chief Keith, including outlets, fixtures, and wiring systems. These were dug from the debris and examined individually. They found one fluorescent light fixture that showed a high concentration of heat. It was disassembled and examined at the scene. The ballast—a small device that regulated the electric current in the light—appeared to be not functioning properly. It was sent to a laboratory and found to be faulty.[36] The consensus of the investigators was that the fixture was the source of ignition.

Chief Keith explained that the row of fluorescent lights was left on overnight and most likely for security reasons. When the wood was ignited from the shorted transformer, the fire didn’t accelerate because there wasn’t enough oxygen inside the false ceiling.

“The fire had probably been smoldering quite some time,” he said, “but it couldn’t get quite enough air to burn.” When the manager of the Raleigh Bazaar opened the building and started the air-conditioner, the incoming air “scattered [the fire] throughout the building.”[37]

Chief Keith added that the fire did not result from the violation of any fire code or building code. “[Fire marshals] could have inspected the building [days before] and never detected anything.”[38] Had the building been newly constructed, however, that type of ballast would not have met code requirements, because it didn’t have a device for preventing overheating.

The age of the ballast was estimated between ten and thirty years. Fluorescent light fixtures were not subject to being checked by the city for defects, nor could problems be detected prior to a malfunction, noted Dr. J. Samuel McKnight of Research Engineers Incorporated, a firm retained by the fire department for investigation. Signs of problems, he added, included dimming or browning out of the entire light, or a “sudden asphalt-like odor.”[39]

The investigation team consisted of Chief Owens, Raleigh Police Department Detective W. G. Arnold, and four engineers from the RTP firm: Gary M. Moss, John Aiken, Woody Rapp, and Dr. Herb Hill.

The investigation started at 11:30 a.m. on the day of the fire, when Chief Owens met with Detective Arnold at the scene. Crews were still battling the blaze. After the fire was extinguished, they began combing through the rubble. They focused on the rear north end of the building due to burn patterns they found there, and reports from seven witnesses who saw smoke coming from there.

The process of the investigation included recording statements from the first-arriving company officer, building tenants, electrical repairmen, and other witnesses. The investigators also examined the debris from the building, and conducted a laboratory analysis of items removed from the fire scene.

Reported

the Raleigh Times on July 14, clean-up at the site was scheduled to

begin the next day. A real estate company was handling the effort and the site

would likely be turned into a parking lot, said Sid Gulledge of North Hills

Realty. A parking lot would reduce the tax liability of the vacant site, and

generate revenue to compensate for the income no longer received from tenant

rentals.

Reported

the Raleigh Times on July 14, clean-up at the site was scheduled to

begin the next day. A real estate company was handling the effort and the site

would likely be turned into a parking lot, said Sid Gulledge of North Hills

Realty. A parking lot would reduce the tax liability of the vacant site, and

generate revenue to compensate for the income no longer received from tenant

rentals.

The property was owned by the Shepherd Estate, and specifically owners William Vass Shepherd of Coral Gables, FL, and James E. Shepherd of Alexandria, VA. It was leased to Boston businessman Matthew C. Weisman, who had an option to buy the Mangel’s Building, the parking lot next door, and the adjoining building that housed the Bookmark and the old Coleman-Womble clothing store. Mr. Weisman declined to reveal his plans for the properties and options. The News & Observer noted on July 8 that a consultant’s study of the mall area had recommended that a high-rise office building be erected on the property.

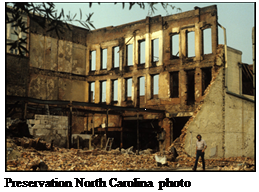

Starting on July 15, demolition crews would begin tearing down the remaining walls. Some of the work would be done at night, due to daytime heat, congestion on the mall, and traffic on nearby streets. The demolition was requested by the city as the site was deemed a public safety hazard. They also wanted to remove the barricades that were blocking part of the mall.

The site was expected to be cleared within the next ten days.

As the heavy smoke spread through the downtown blocks on the day of the fire, soot accumulated on hundreds of cars. Four days later, the Raleigh Times reported on their owners attempts to clean their vehicles. Tommy Frazier, who owned Country Caterers on Salisbury Street, found his white 1968 Cadillac covered with specks of black tar. “I’m just sick with it,” he said.[40] Raleigh resident Jerry Casper found his light blue 1974 Plymouth covered with black ash on Salisbury Street. He used degreaser and a laundry product to clean the car, but that left many spots still standing. “That tar is sure hard to get off,” he said.[41]

The manager of the Constan Car Wash on Peace Street said he’d seen a number of tar-spotted cars since the fire. “We got fifteen or twenty [the next day],” said Larry Martin.[42] He said his staff hand-washed the cars first, then applied Varsol and wax. Not all of the tar could be removed, however. “Most of the customers are keeping receipts for their insurance company.”[43]

Dusty’s Detail Shop was using a chemical on cars, then applying an abrasive paste followed by buffing to remove all dead-looking paint. Then they washed and hand-waxed the cars. It cost as much as $150, due to the amount of time needed.

Chief Keith said the apparatus at the fire was easily cleaned with detergent. He added that the trucks were always kept clean and polished. “The polish,” he added,” keeps the stuff from sticking to the paint.”[44]

“Fire causes officials to ponder increasing building inspections,” read the headline in the July 10 edition of the News & Observer.

Raleigh building inspector W. F. Harrelson said that increased inspections could be a deterrent against future fires, because some code violations—such as failing to use fire-resistant materials in renovations—likely go undetected in some of the older buildings downtown. Some owners limited the amount of work on older buildings, so they didn’t have to conform to newer fire codes.

“If a building has in excess of fifty percent of its value done in repairs and alterations” within a few years, said Harrelson, then the entire building was required to conform to current building and fire safety standards.[45] Added Chief Keith, some owners were careful “to renovate piecemeal, to build a little at a time,” so they only had to meet the older and less-restrictive building codes.[46]

Harrelson noted that the city inspections division would need more people, and such a project would be a major undertaking.

Presently, city inspectors made no regular checks of commercial buildings for building code violations. Fire inspectors, however, conducted checks for violations of fire codes, such as “exits, combustible materials, some electrical socket storage, sprinklers, furnaces, and other heating equipment,”[47] said Chief Keith. The fire department tried to complete two fire inspections per year, he added.

City Manager L. P. Zachary Jr. said increased inspections of buildings downtown were “something we probably need to look into.”[48]

Out of the forty-six buildings on the Fayetteville Street Mall, twenty-two were similar in construction to the Mangel’s Building. They were designated Class 2 for insurance purposes, meaning built primarily with masonry and wood for support, roof, and flooring, noted William D. Lanier of Insurance Services, the agency that established insurance rates for commercial buildings based on their construction and occupancy.

Many of the other Class 2 buildings on the mall were also built around the turn of the century. They included Raleigh Books Inc., Brittain’s Cosmetics, Kimbrell’s Furniture, Holly’s Hallmark Card and Gift Shop, Ron’s Fast Foods, Johnson’s Jewelers, Land’s Jewelers, McCrory’s, Briggs Hardware, the Bookmark, Ole N.C. Cafeteria, Christian Science Reading Room, Rusty’s Restaurant, and the old Coleman-Womble building.

The Raleigh Times on July 8 quoted Chief Keith saying that the blaze “used more firefighters and equipment than any fire in the city’s history.” He added to the News & Observer, it was the biggest one he remembered downtown since the K&W auto garage burned on Blount Street in the early 1950s.

James Briggs had a different opinion. “The biggest one came with the Yarborough House fire on July 3, 1928,” he told the newspaper. “And [the Mangel’s fire] was a peewee compared with that one.” He also cited Efirds department store. “It burned in the afternoon and there were a lot of people trapped, and they had to get them out before they could start fighting the fire,” Briggs said. The building burned to the ground, he recalled.

Because he had bronchitis the day of the fire, the 77 year-old stayed in his store, which was about a block down the mall. “With the way things are going,” he told the newspaper, “looks like we’re going to have another parking lot.”[49]

What were some of the comparable major fires, before or after?

Excluding the blocks-long conflagrations in the early 1800s, the largest fire in the city’s modern history was Pine Knoll Townes on February 22, 2007. Six alarms were struck for a fast-moving, wind-fed fire in a developing townhome community off Capital Boulevard. Thirty-two homes were seriously damaged or destroyed. Twenty-nine families and 72 people were displaced. Damage exceeded $4 million.

Other large and resource-intensive fires of the last century:

|

·

Shelton’s Furniture Company - 1993 ·

Gorman Crossings Apartments - 1993 ·

Wake County Courthouse - 1990 ·

Peebles Hotel - 1970 |

·

Manmur Bowling Center - 1959 ·

Yarborough Hotel - 1928 ·

State Insane Asylum - 1926 |

Cross-era comparisons are difficult, however, due to different metrics for measuring fires and firefighting resources. See this blog post http://www.legeros.com/ralwake/photos/weblog/pivot/entry.php?id=2881 for a more detailed analysis.

See the appendixes for information about other fires on Fayetteville Street.

Fayetteville Street was the city’s main thoroughfare south

of the Capital in the early 20th century. By the 1950s, however,

parallel streets such as Salisbury Street and Wilmington Street were more

heavily travelled.

Fayetteville Street was the city’s main thoroughfare south

of the Capital in the early 20th century. By the 1950s, however,

parallel streets such as Salisbury Street and Wilmington Street were more

heavily travelled.

In 1966, the one-block cross-street Exchange Street was converted to a plaza, testing the concept of installing a pedestrian mall on Fayetteville Street. The idea was explored by business owners as a revitalization strategy. Downtown businesses had been impacted by the opening of shopping centers and malls in Cameron Village in 1947, at North Hills in 1966, and later at Crabtree Valley in 1972.

On January 1, 1976, Fayetteville Street was closed to traffic. Pedestrian malls were a successful innovation elsewhere in the country, and city leaders hoped this would bring people back downtown. A civic center would also be constructed in the middle of the south end of the mall, as a new gathering place for the growing city.

The Fayetteville Street Mall opened in November 1977. The

gradually descending roadway had been replaced by sequential plazas separated

by short staircases. Features were added, including sculptures and fountains, planters

and sections of grass, and tables and benches made of granite. The mall also

contained a fire lane that could accommodate emergency vehicles.

The Fayetteville Street Mall opened in November 1977. The

gradually descending roadway had been replaced by sequential plazas separated

by short staircases. Features were added, including sculptures and fountains, planters

and sections of grass, and tables and benches made of granite. The mall also

contained a fire lane that could accommodate emergency vehicles.

The pedestrian mall raised expectations of a renewed shopping corridor, where people could walk without the impediment of automobile traffic. Within a few years, however, the level of business activity had returned to pre-1977 levels. The street stayed busy during the workday with office workers, but was largely empty after 5:00 p.m. Eventually, such landmark stores as Hudson-Belk and Briggs Hardware closed or relocated.

In 2006, the street reopened to vehicle traffic. The grand opening was held on July 29, after a two-year project that returned the street to its original form. As part of a new downtown revitalization project, the outdated and undersized Raleigh Civil Center was also demolished. Fayetteville Street was again bookended by the State Capitol and Memorial Auditorium.

Elizabeth Reid Murray photo

(left), City of Raleigh photo (right)

In 2008, the Fayetteville Street Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places. It’s comprised of the 100 to 400 blocks of Fayetteville Street, the 0-100 blocks of the south side of West Hargett Street, the 00 block of the north side of West Martin Street, and the 100-400 blocks of South Salisbury Street.

The historic district contains mostly commercial establishments, and includes eleven buildings individually listed on the national register.

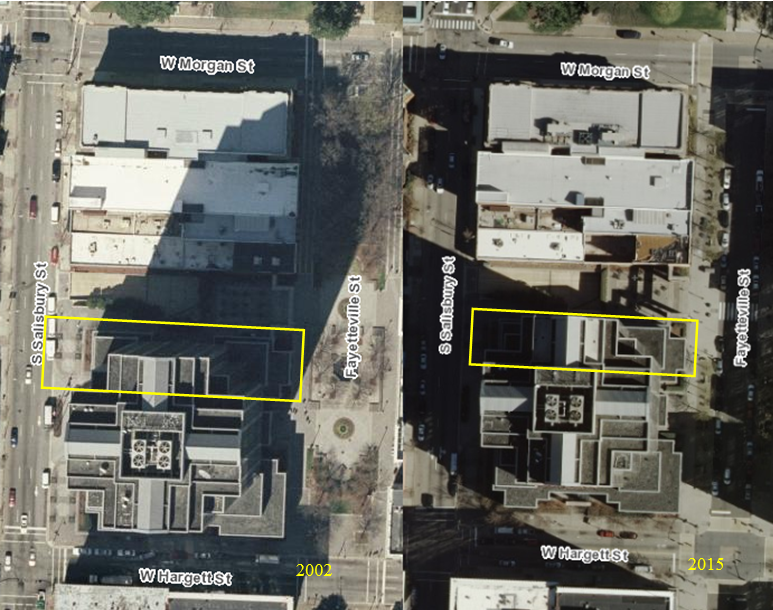

After the Mangel’s Building was demolished, the site was converted to a parking lot, which expanded the size of the adjoining parking lot. The remaining buildings south of the site were removed in or after 1988, and a thirty-story skyscraper was erected on the site. Completed in June 1990, the Wells Fargo Capitol Center is addressed 150 Fayetteville Street. It was one of downtown’s two tallest buildings for nearly twenty years, and is currently the third tallest building in the city.

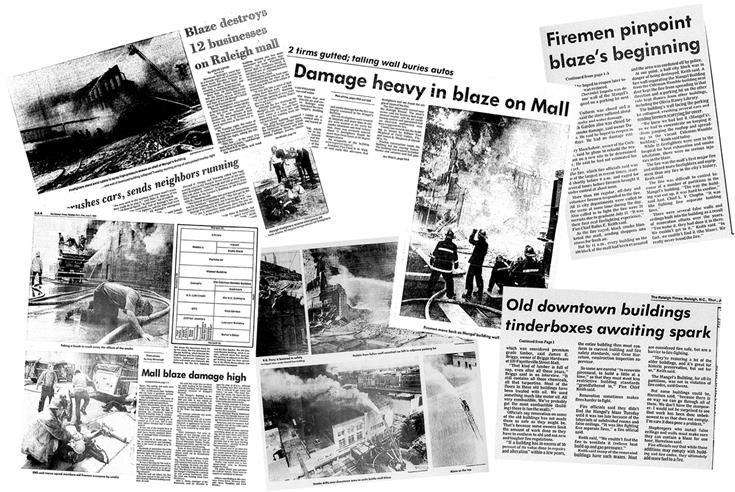

Raleigh Times:

· July 7, 1981 - Damage heavy in blaze on mall

· July 8, 1981 - Probers pinpoint fire origin

· July 9, 1981 - Tinderboxes - Downtown’s turn-of-the-century, pine-timbered buildings ‘designed to burn’

· July 9, 1981 - Firewall measure of luck for some businesses

· July 10, 1981 - Lighting blamed in blaze

· July 11, 1981 - Fire’s fallout takes toll on parked cars

· July 14, 1981 - Mall fire clean-up to begin Wednesday.

News & Observer:

· July 8, 1981 - Blaze destroys 12 businesses on Raleigh mall

· July 8, 1981 - Fire crushes cars, sends neighbors running

· July 8, 1981 - Fire spreads woes to nearby businesses

· July 9, 1981 - Fire probe focuses on air conditioning

· July 10, 1981 - Fire causes officials to ponder increasing building inspections

· July 11, 1981 - Probers say light fixture caused fire

· July 15, 1981 - Fire cleanup set for today

·

July 18, 1981 - Cleanup begins.

Other sources include:

· City of Raleigh News Release, July 10, 1981

· National Register of Historic Places, Fayetteville Street Historic District, http://www.hpo.ncdcr.gov/nr/WA4309.pdf

· Oral histories

· Raleigh city directories.

· Raleigh Fire Department history by Mike Legeros, http://legeros.com/ralwake/raleigh/history

· Raleigh Fire Department records

· Raleigh Fire Museum information, http://raleighfiremuseum.org/content/mangel

· Raleigh Public Record, Development Beat: Wayback Wednesday — Raleigh’s ’77 Civic Center, http://raleighpublicrecord.org/news/2016/07/27/development-beat-wayback-wednesday-raleighs-77-civic-center

· Sanborn fire insurance maps.

· Vanished Raleigh, Photographs by Elizabeth Reid Murray, http://legeros.com/vanished-raleigh

· Wake County GIS records via iMAPS web site, http://www.wakegov.com/gis/imaps

· Wake County real estate records via Search Real Estate Records web site, http://www.wakegov.com/tax/realestate

· Wake County Roads, Fayetteville Street, http://www.wakecountyroads.com/fayetteville.html

· Wikepedia, Fayetteville Street Historic District, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fayetteville_Street_Historic_District.

Note: The accompanying portraits are from 1984, and appeared in a commemorative book about the fire department that was published that year.

Retired Captain Donald Summers (2010) was a new firefighter at the time of the fire, hired a year earlier. This is adapted from an oral history interview conducted on April 21, 2010.

This call came in for a structure fire at Fayetteville

Street. [50]

They gave the address. Of course, they didn’t give a building name for it, but

they gave the address. I was riding on Engine 1.

This call came in for a structure fire at Fayetteville

Street. [50]

They gave the address. Of course, they didn’t give a building name for it, but

they gave the address. I was riding on Engine 1.

We rounded the corner, came across Morgan Street up there, and turned on Salisbury. You could see it was just faint smoke. It wasn’t heavy and Captain [Nick] Glover came off the truck and gave a “Code One.” And we pulled up there, and we pulled a booster line. Connie Altman and I went inside with the line, through the back door on the Salisbury Street side.

I remembered walking inside and into the back of the building, and I could see all the way in through to the mall. There was still people in the store. There was a “world bazaar” in that building, a flea market-type thing. Light haze was inside and I told those people, “Hey, y’all need to get out of this building.”

Because, obviously there was something burning, and we didn’t know what it was. I wasn’t in there very long, just a couple minutes, and all of a sudden that smoke started getting heavier. Heat started coming, but we never could see any visible flames.

So I came back out and said to Captain Glover—they called him “Boss”—and I said “Boss, I think we’re going to need more ammunition. That booster line ain’t going to be enough.” He said “what do you mean?” I said “it’s kinda heavy in there.”

He was outside, sizing up his building. And so Altman and I went back in with the inch-and-a-half [hose line]. Obviously not spraying any water yet, because you didn’t see anything. We didn’t know where it was. And we didn’t advance very deep into the building, because it was a multi-story structure.

We had Engine 3 responding with us. They went to the Fayetteville Street side of the mall. And back then it was a [pedestrian] mall. It wasn’t a street, it was a mall. So the engine had to get up on the mall itself.

I remember then the smoke got solid black, and it was down to the floor. You couldn’t see anything. And I came back out and told “Boss, whatever it is, it’s not enough.” We were going to have a get a two-and-a-half-inch. I’ll never forget his hands, looked just like this. Like, what in the world has happened here?

That’s when things started showing. And smoke was coming through the mortar and you knew you had a really massive high-rise fire. The whole building was engulfed in flames.

We started making advances with the two-and-a-half-inch, as I saw fire breaking through the ceiling of the first floor. We got about three feet into the building when an explosion of heat blew us back. We rolled backward about ten feet and landed in front of the engine.

And I’ll never forget, I saw that our driver Creighton Edwards had set up a sprinkler system on top of the truck with a booster line to keep the truck cool. It must have been pretty hot [from the radiant heat]. Engine 1 never moved from that spot. They had a hydrant right there.

It didn’t take long for us to realize that we had to go to a defensive mode and come back out, and fight this thing from the outside.

That’s when the ladder came in. Old Truck 1, the platform. They set it up [to spray water from above]. Lo and behold, when they set it up, there I stood.

Back in those days, they just looked for anybody to go in the bucket, any two bodies. I just happened to be standing there. Chief Walker saw me standing there. It was me and Janice Olive. He said “I need you to go up in the bucket.”

I’d been up in the bucket before. I had trained on the bucket, because it was a piece of equipment at Station 1 and we trained on it. Everyone at Station 1 trained on all of the trucks, no matter if you were assigned to the engine or the ladder. So I went on up in the bucket.

I’ll never forget, we were raised to the top of that building, and you could see it was opening up. The flames were coming out, and it was getting hotter and hotter and hotter. There were two nozzles on the bucket. I had the left fog nozzle and she had the right. The left one couldn’t be angled on the building, it was just a waste. It was flowing water, but it wasn’t being directed on the fire.

There was a kill switch at the turntable, to give the driver control of the bucket. So he was moving it around. He knew he had too much experience, and there was no way in the world he was going to let us [the firefighters in the bucket] have control of the aerial.

Pretty soon, I looked behind me and my turnout gear started smoking. It was hot. There was also a heat shield underneath that bucket. And little sprinklers under the bucket. In the intercom system, I said “You might want to bring us down.” And he thought I said “You might want to bring us around.”

So we were moved even closer to the fire and I was like “Oh my gosh, this is not where we need to be.” And it really became really hot, and apparent that we were going to burn up in this bucket. And if I’m hot, what’s it doing to the ladder?

That’s when they began to see that the side of the building was bulging. And they brought us down. They got that truck out of the alley, because the wall was going to fall.

I’ll never forget when I hit the ground. I mean, I just jumped out of the bucket and just collapsed, because the heat was so… I was totally exhausted, after making the initial attack and going into the fire, and doing that for a good 20 or 30 minutes, and then doing this bucket job. I just collapsed on the sidewalk.

We were in the bucket about fifteen minutes. We went over to the rehab area, which was on the opposite side of Salisbury Street. EMS was administering oxygen and giving towels to firefighters.

I got taken to the hospital. Several of us got taken to the hospital. Rescue 7 transported me, Altman, and two or three others to Wake Medical Center.

When we got there, of course, you were feeling better. Rehydrated. The nurse came around to give us a carbon monoxide blood test. I just figured that was no more than a finger stick or something. Okay, that’s cool.

And I’ll never forget, as long as I live, she put this needle about six inches long down in my artery, and I like to come off of that table. It was funny enough that Connie Altman and those boys were over there laughing. Calling me a sissy and everything else. I said “Wait’ll you get one too.” [Asks the interviewer, how did they do?] “I watched them draw up.”

None of these guys ever had anything like that before, a carbon monoxide test. I said “Well, I never did get overcome by smoke,” I said, “I’m just hot.”

I never had another one since then. I always said, “I’m not doing that again.” After leaving the hospital, I was sent back to the station. I was only on scene for about 45 minutes.

Retired Battalion Chief A. Randy Wall (2009) was a Driver at the time of the fire, in the fifth year of his career. His 1984 portrait reflects his subsequent rank of Captain.

I was a Driver/Engineer assigned to Truck 5 on “C” shift

on the day of the fire. On that Tuesday, Captain Wayne Best and myself were the

two personnel working on Truck 5. Although we had repeatedly warned command

staff that there needed to be a minimum manning of three personnel on that

apparatus, we routinely rode with only two. On this day, I was driving the

front and Captain Best was driving the tiller.

I was a Driver/Engineer assigned to Truck 5 on “C” shift

on the day of the fire. On that Tuesday, Captain Wayne Best and myself were the

two personnel working on Truck 5. Although we had repeatedly warned command

staff that there needed to be a minimum manning of three personnel on that

apparatus, we routinely rode with only two. On this day, I was driving the

front and Captain Best was driving the tiller.

We had pulled Truck 5 onto the apron at Station 5. After checking off the truck, I bled the air brakes. As I recall, while going through the usual routine of check off and brake maintenance, Engine 1 and Engine 3 were dispatched to a smoke investigation at the Mangel’s building. Captain W. N. “Nick” Glover reported a “Code One” upon arrival. This designation meant that the situation could be handled with either a booster or a one-and-a-half-inch line.

I remember his report because Nick was a fairly new captain and we often joked afterwards that if he ever marked a “Code Two” upon arrival, we would all mark out sick immediately. As it turned out, this was Captain Glover’s first working fire as a captain.

Captain Glover saw a small amount of smoke coming from the roof area. A woman exited the building and stated that the air conditioner was on fire. They had had problems with it for a few days. Captain Glover instructed Firefighter Donald Summers to pull a booster line. They encountered a locked steel door that could not be breached. No one had a key. Things got ugly very quickly from there. When Captain Glover requested that Truck 1 be dispatched, the chief officers were alerted by that request that something was going on.

As I was completing the bleeding of the brakes on Truck 5, several personnel ran outside to say that Engine 1 was calling for additional companies due to heavy smoke conditions. As I recall, Assistant Chief Norman Walker requested Truck 5 to respond. When I acknowledged the call, I reported that Truck 5 was en-route with two personnel. My reason was to remind them that we had minimum manning of two personnel in case they were expecting a full company to arrive.

Truck 5 was directed to respond to the Fayetteville Street Mall entrance on Morgan Street. Upon arrival I had line of sight contact with Chief Walker who was in command at that time. He did not have a hand-held radio. After a couple of confused hand signals—a waving motion to come to him and my thinking that he wanted the truck to stage at his location—I realized he wanted me to physically walk to him to receive further instructions. Upon walking to his location, about midway between Morgan Street and the Mangel’s building, he instructed me that we were to come and assist with the advancement of hand lines into the front of the Mangel’s building.

I ran back to Truck 5 and related to Captain Best what Chief Walker had requested. We both donned air packs and walked to the Mangel’s Building, and began assisting with advancing hand lines into the building. After Truck 5 arrived, Engine 5 was dispatched to the fire on another alarm. As Engine 5 arrived on Morgan Street, Chief Walker asked me to go across the mall and through a parking lot on Wilmington Street, and guide Engine 5 onto the mall and to a hydrant on the mall.

I removed my air pack and placed it on a park bench. I then jogged to meet Engine 5 and led them to the requested location. We began pulling lines from Engine 5 when Chief Walker requested that Truck 5 come onto the mall and position directly in front of the Mangel’s building. Captain Best and I walked up the mall to Truck 5 and drove around to Wilmington Street and through the parking lot onto the mall. We were directed to position perpendicular to the middle of the building and set up the ladder for aerial operation of the ladder pipe.

We positioned the ladder truck as requested. On Truck 5 we had three-inch hose strapped to the bed of the ladder and attached to the ladder pipe and a 500 GPM fog nozzle. We placed the triple Siamese beside Truck 5, and placed the hose clamp on the three-inch line. As either Engine 10 or Engine 12 laid the lines to the “triamese” [or three-way valve], I mounted the ladder and Captain Best manned the turntable. I distinctly remember thinking that I should have taken the time to retrieve my air pack from the park bench before mounting that ladder.

As we were preparing for aerial operations on the mall side, smoke was coming from every nook and cranny of the building. It was what I called “angry smoke,” looking for a way to escape in volume rather than oozing from every crack in the mortar and around windows. As the ladder rose above the roof line, I observed the angry smoke coming from the seams in the flat roofing material. The fire had not vented itself through the roof at that time.

I remember thinking that I would have to wait for the fire to vent itself before I could flow any water. And even then, I would not train my stream into the vent opening, as was often seen on most aerial operations, because I knew the devastating effects that would have on everyone fighting fire inside the building.

Suddenly there was a sound from inside the building that sounded like a roll of thunder. At that moment, smoke began billowing from the windows on the mall side. I knew that there had to have been a collapse of a ceiling or a floor above the fire. Instantly I was in trouble because I had no air pack. I was completely engulfed by the heat and smoke, hoping and praying that the fire would not vent through the windows as well.

My three-inch line to the ladder pipe was flat, no water. If I only had water, I could protect myself from the heat and smoke. My vision was completely obscured by the smoke. I couldn’t see the bottom of the ladder and no one on the ground could see me. I had seen a metal canopy to my left, two floors below, attached to the building adjoining the Mangel’s building. Still my line was flat.

I had no radio communication with the firefighters below. We had hand signals that we used to communicate with the person operating the turntable. I couldn’t see Captain Best and he couldn’t see me. If only the smoke would clear long enough for me to locate that canopy again, I could jump to the canopy. One may wonder why I didn’t just climb down the ladder. I was certain that there had to be fire on the ladder, judging by the heat I was receiving on the tip of the ladder. Still no water, my line was flat.

Desperation set in. I was screaming to move the ladder. No one could hear. I was whistling as loud as I could, anything to call attention to the ladder and the person on it, me! Still, no water to the ladder pipe.

Everything seemed to slow down into slow motion. I had my face in my coat to filter the smoke as best I could. My forgetting the air pack seemed to be a potentially fatal mistake. Continuing to holler and whistle for a few more moments, I resigned myself to the inevitable fate that seemed to lie just before me. I was becoming very weak. Still, no water. I relaxed and leaned back letting my life belt support me. This was it, I thought.

Suddenly, water! The three-inch lined swelled with water. I had already placed the handle in the nozzle so I pulled it back, elevating the nozzle and so I could change the pattern from a straight stream to a 90-degree fog pattern to give me relief from the smoke and heat. I couldn’t muster the strength to adjust the pattern on the nozzle. I gave it all I had.

I finally just let go of the handle on the nozzle and let the 500 gallons-per-minute of water spray straight down below. When the stream of water kept hitting the sidewalk, one of the chiefs instructed Captain Best to move me out of the smoke to see what the problem was. Clear air and blue skies were a true lifesaving blessing for me that day. I now know the meaning of “just in the nick of time.”

Firefighter Clyde Leonard from Engine 5 relieved me on the ladder and I went to the EMS unit on the mall. A little water and a few minutes rest and I would be good to go. District Chief Merton King and the EMS crew, however, would not allow it. I told Chief King that I would have to go tell Captain Best that I was going to the hospital. Chief King would not let me. He said I would leave and not come back, and he would tell Captain Best.

Firefighter Kenny Jones and I were the first firefighters transported to Wake Medical Center that day. I figured we would be the only ones. Not long after we arrived, the emergency room began filling up with firefighters from the fire. They performed the dreaded arterial blood draw for the carbon monoxide test. It was painful, but I considered myself lucky to be able to feel pain. After a while the doctor told me I could leave, but that I could not return to duty that day. Kenny and I caught a ride back to the fire with an EMS unit.

While in my little space at the ER, an administrative employee brought me a telephone and said I had a call. It was my wife. She was a nurse at an OB/GYN office and one of the employees had come in talking about the bad fire on the Fayetteville Street Mall. Something was said about one entire block had burned and that the radio news reports were saying that the entire mall was in danger.

At her office they kept a radio in the lab. My wife quickly turned the radio on. The first words she heard were that “The scene is reminiscent of Vietnam. Firefighters are laid out everywhere. Many have been taken to the hospital. Many were seeking refuge from the sweltering 90+ degree heat and stifling humidity in what little shade was available.” My wife called Station 5. When she didn’t get an answer she called Station 11, where I had worked a few months earlier before getting promoted to Driver/Engineer.

She asked Captain Whittington if he knew if I was at the big fire downtown, knowing full well I had to have been dispatched. When he answered that Truck 5 was at the fire, she asked if he knew whether or not I was still there or had gone to the hospital. He told her he had no way of knowing.

However, all Fire Prevention personnel had been ordered to go to a fire station with their turnout gear to help man the apparatus. They were placing reserve apparatus into service by going around and picking up personnel from each station. The Fire Prevention personnel would fill the vacancy created by the firefighters manning the reserve engines.

The fire inspector that reported to Station 11 had come from downtown. He told the guys at Station 11 that he traveled down Wilmington Street, and that whoever was on the ladder on Truck 5 was catching hell, because you could only see the bottom half of the ladder. The top half was in total black smoke. Of course, Captain Whittington didn’t tell my wife that, but he knew it was probably me. She took a chance and called the ER and they let her talk to me. I assured her I was alright and would be returning to the station soon.

Kenny Jones and I waited on the curb at the entrance to Wake ER. We caught a ride with EMS. Kenny rejoined his company at the fire. Truck 5 had returned to the station and I ended up back at the station. District Chief Buck King called shortly after my return and asked me what the doctor had told me. I told him I was told to go home, but that I was fine and we were short of personnel so I would stay. He said okay and I stayed and finished the shift.

That’s my experience that day. I remember most of it very vividly.

Retired Captain Alonzo Moore (1992) was a Driver at the time of the fire, and the sixteenth year of his career:

I was the driver of Engine 12 and we had gone down to the training center that morning. And when we heard all the radio traffic, and nobody showed up to train, we went back to the fire station. As we started backing in, Captain says on the radio, “we’re ten eight, back at Station 12.” And Chief Keith came on the radio and says “Come to Fayetteville and Hargett Street.” And by that time, I believe we could see the smoke.

So we went downtown. There was a hydrant right in the

middle of the mall, on Hargett Street. That’s where I stopped and where we

connected, with the two lines like we did then.[51]

So we went downtown. There was a hydrant right in the

middle of the mall, on Hargett Street. That’s where I stopped and where we

connected, with the two lines like we did then.[51]

They pulled off every line off my truck. First the inch-and-a-half and then they started pulling the two-and-a-half and taking it with the nozzle and so forth. And they took it out of sight. I couldn’t see where it went.

Then somebody came back and told me to go ahead and charge the line. So I did. Truck 5 was also there, and set up on the mall. And when I charged the line, water started coming out at the top of the ladder. I closed it, I opened it. And I realized that the line had somehow been connected to the truck. I thought they was fighting fire [inside] with it. But you know how the lines were all like spaghetti, you couldn’t tell where any of them were. But I figured out through opening and closing that it was connected to Truck 5.

I also remember a lot of people gathered out and watching. And the wall fell down. You know how when you open an oven, and you got your glasses too close to it, and it fogs your glasses up? It was just like that. Well, when that wall fell down, a blast of heat [came] out. I mean, just came rolling out of there. And everybody was running and trying to get away. There must’ve been fifty or more. And I thought, well darn, since I was standing out there, I grabbed my coat and put it on. ‘Cause, what was going to happen next? That blast was hot!

Retired Captain G. Michael Davis (2010) was a recruit in class at Station 2 on the day of the fire.

Twenty-three years after the fact, I still have vivid memories of fighting my first structure fire.

It was a Tuesday morning and the class of 1981 was due to

graduate the Academy in ten days. Three and-a-half long months of training were

about to come to an end and each of us eagerly awaited, with anticipation and

excitement, our first station assignments. There was a guest instructor

teaching our last formal class before graduation.

It was a Tuesday morning and the class of 1981 was due to

graduate the Academy in ten days. Three and-a-half long months of training were

about to come to an end and each of us eagerly awaited, with anticipation and

excitement, our first station assignments. There was a guest instructor

teaching our last formal class before graduation.

The subject of his lecture escapes me, because along with everyone else in the room as well as everyone else in the fire department that day, information blaring from an overhead speaker commanded our attention. The voice from the speaker broadcast an alarm announcing what I remembered as “Headquarters to Engine 1, Engine 13, Rescue 7, Car 52, Reported structure fire, Mangel’s building, Fayetteville Street Mall.”[52]

I had learned over the past three-and-a-half months not to become too excited until the first engine company arrived on the scene, and transmitted a “fire code.” I tried to ignore the distraction created by the emergency dispatch and focused my attention back on the class facilitator as he lectured from his podium. The first arriving engine announced “Engine 1, 10-23, condition red, light smoke showing.”

The report of smoke showing made the already difficult task of listening to the instructor all but impossible. Despite the drama being transmitted over the radio our instructor seemed oblivious to the fact that no one was paying attention to him. All ears in the room save his strained to hear every sound that reverberated from the speaker, which had become our nexus to the landmark event taking place two short miles from where we sat. We had become envious observers of an event in which we desperately wanted to participate.

The Mangel’s Building was a three-story structure erected in the early 1900s. It was comprised of brick and wood frame construction. During the years preceding its incineration, the building had accommodated office spaces as well as other types of mercantile and commercial businesses. As with many buildings of its type and age, it had been renovated and reconfigured many times during its existence. The installation of partition walls and false ceilings in particular would prove fatal to the building. These renovations delayed preliminary efforts to find the fire and subsequently hindered efforts to extinguish the inferno once it was found.

The Mangel’s Building was situated almost directly in the center of downtown Raleigh. The building was flanked to the east by a pedestrian mall, which on sunny days became filled with people sitting on park benches, or walking up and down the mall lost in conversation, window-shopping or just enjoying the day. There was a small alley used for parking on the north side of the structure. Salisbury Street, a thoroughfare leading south out of town, bordered the west side of the building. The south side shared a party wall with other shops and businesses. The proximity of these shops and businesses to the conflagration occurring directly beside them created cause for concern, as the fire could easily spread one building to the next eventually consuming the entire city block.

The fire companies dispatched on the first alarm had been on the fire scene now for several minutes. Reports on smoke conditions, initially described as light, were revised as conditions inside the building rapidly deteriorated. Interior attack teams reported poor visibility and steadily increasing temperatures. The fire was generating smoke in ever-increasing quantities.

It was obvious that the fire was growing in intensity. However, the fire companies who had advanced attack lines into the structure were still unable to reach the seat of the fire. Using pike poles, interior attack teams began to breach the ceilings on the first floor of the building. Pike poles are harpoon-like tools of various lengths, used to pull down ceilings and punch through walls in order to locate hidden fires.

Upon breaching the ceiling, the fiery beast revealed itself. By this time the fire had grown beyond the capacity of the initial emergency response to extinguish. As crews worked inside to deprive the fire of its hiding place, the magnitude of the situation and the potential for destruction became all too apparent. Once again we heard the overhead speaker in our classroom spring to life trumpeting the need for assistance. “Command to Headquarters dispatch a second alarm to this location.”

Despite the best efforts of all involved, the fire was now raging out of control, and it soon became necessary to dispatch a third alarm. Due to the large numbers of personnel and equipment required to fight the fire, the Incident Commander requested and received a mutual aid response from surrounding fire departments to cover those parts of the city left without fire protection.

Our entire freshman class was surprised when the classroom speaker suddenly broadcast an announcement that all of us longed for, but none of us expected. Seven words that would signal an abrupt end to our training and mark the practical start of our careers as professional firefighters. The order was given without protocol or fanfare, “Captain Honeycutt get your rookies down here.”

Every rookie in the room leaped to their feet as if jabbed with a cattle prod. We rushed out of the room leaving the guest lecturer standing alone at his lectern. Each of us loaded our gear into the back of cars and pickup trucks, along with any other means of transportation available to deliver personnel and equipment to the fire scene.

As we approached the intersection of South Wilmington Street and Pecan Road, we crested the top of a hill overlooking the city. There was a thick gray haze that created a murky view of downtown Raleigh. A huge column of smoke rose several hundred feet above the city. The feeling of anticipation and excitement was palpable. It all seemed surreal.

Becoming a firefighter was not a lifelong dream for me. The truth is that I had never even considered the prospect until a friend suggested the idea, but here I was, rushing headlong towards an event that would completely reshape my thoughts and opinions on where my life was headed.

Once on the fire scene, the officer in charge of staging divided the rookie class into squads, assigning us to various operational teams already fighting the fire. I joined a team of veteran firefighters preparing to advance a two-and-a-half inch hose line directly into the “belly of the beast.” We entered the building through a mezzanine reminiscent of department stores I had visited with my mother as a child. Glass enclosures created a gallery of about fifteen feet in depth, which in years past displayed mannequins and merchandise. To me it created a pitch black tunnel that invoked fear.

As we entered the dragon’s lair, we crawled on our hands and knees, wrestling with the hose we used as an attack line. The two veterans firefighters to whom I had been assigned conducted themselves with an air of authority and confidence that created within me a sense of trust. Though I had never met ether one of them, I accepted their judgment and direction without question. I saw little choice in the matter as I had no clue as to what I was doing, or of the dangers that might await us. I instinctively knew that my best chance for survival depended upon their experience, and upon my listening to their advice and instruction.

As we reached the far end of the mezzanine, we took a position where we could direct a stream of water onto the fire, while using the doorway leading into the building as cover from falling debris. The entire second floor had collapsed, and the fire completely engulfed the interior of the structure. As I stared into the abyss of boiling churning flames, the spectacle left me frozen in awe. It was like standing in the middle of a glowing ember and looking out. The motion and beauty of the flames mesmerized me, as they rolled gracefully around us. I was jolted to awareness by the sound of shouting. One of the veteran firefighters bellowed out from behind me “Open the nozzle, new boy.”

Startled, I yanked the handle, which controls the flow of water from the nozzle, and sent a stream of water spraying onto the raging inferno. The massive hose sprang to life and it was all the three of us could do to hold the hose in place. The stream of water seemed to have little more effect than a water pistol would against a campfire. We straddled the hose while kneeling in five inches of standing water. I remember being astonished at how uncomfortably hot the water felt on my legs. The radiant heat from the fire was so intense that it caused the skin on my face to peel as if sunburned from a day at the beach.

Suddenly we heard a muffled crackling sound. The firefighter directly behind me told me to back out, his voice filled with alarm. As I lifted myself off the charged hose line, on which we had been sitting, it slid out from beneath me like a giant snake striking out in all directions. The hose threw me face down into the murky water. I lifted my head in time to watch the same firefighter, who had ordered my retreat, wrestle the hose to the ground, shutting the nozzle off to keep it from injuring anyone.

I tried once again to stand. As I attempted to lift my body from the floor, I felt the weight and heat of debris that had fallen from the ceiling of the mezzanine onto my legs. The veteran firefighters with whom I had entered the building grabbed me by my armpits, one on either side, dragging me out from beneath the rubble. I tried to regain my footing, but my rescuers hoisted me with such vigor that I could only stumble along between them. The exit was only a few feet away, but to me it seemed an eternity. As we moved toward the light of day it reminded me of books I had read recounting near death experiences and how those who had died moved as we did now towards the light of salvation at the end of a dark tunnel.

By days end, much of the Mangel’s Building was nothing more than a pile of rubble. However, we had kept the fire from spreading to additional exposures, very likely saving an entire city block from destruction. I sat on a concrete wall encircling a large planter contemplating the events of the day. The feeling of exhaustion, both mental and physical, was complete. Until that moment, I had been too busy to pay any attention to how fatigued I was.

A news reporter stuck a microphone in my face and asked me how I was feeling. I looked straight at the camera and proclaimed, “I’m wore slap out!” This display of poor grammar became ammunition for others to embarrass and tease me with for some time to come. Even so, as I surveyed the fireground, and watched fellow firefighters as they collected tools and equipment, the phrase seemed appropriate. We were all wore slap out!

Fighting fire is hot, nasty, exhaustive work that quite often scares the crap of you. Yet, even then I knew that it was the career for me. I can think of few professions more challenging or rewarding than is the business of protecting property and saving lives. We are not always successful in our efforts to rescue the afflicted from calamity, but almost always we are a mitigating force amid catastrophic occurrences. We make it less painful than if we had not been there, and often that is enough.

Retired Captain Cindy Rubens (2010) was also a recruit in class on the day of the fire. This is adapted from an oral history interview conducted on December 21, 2009:

As I cruised through the radio room of Station 2, I heard someone on the radio request that Captain Hunnicutt load hose on the reserve parked out back, bring it to the scene with all the Rookies. I froze in place. Did I hear that right!? I was headed to my first fire!!

We also loaded extra sections of hose in Robert Marshburn’s truck, another rookie, and carpooled from the station to the scene. When the caravan turned north on South Wilmington Street, it looked like all of downtown was on fire!