Read retrospective and research notes from 2017 (103M, PDF)

See other photos, clippings, and the NTSB report in this Google Drive folder.

Introduction

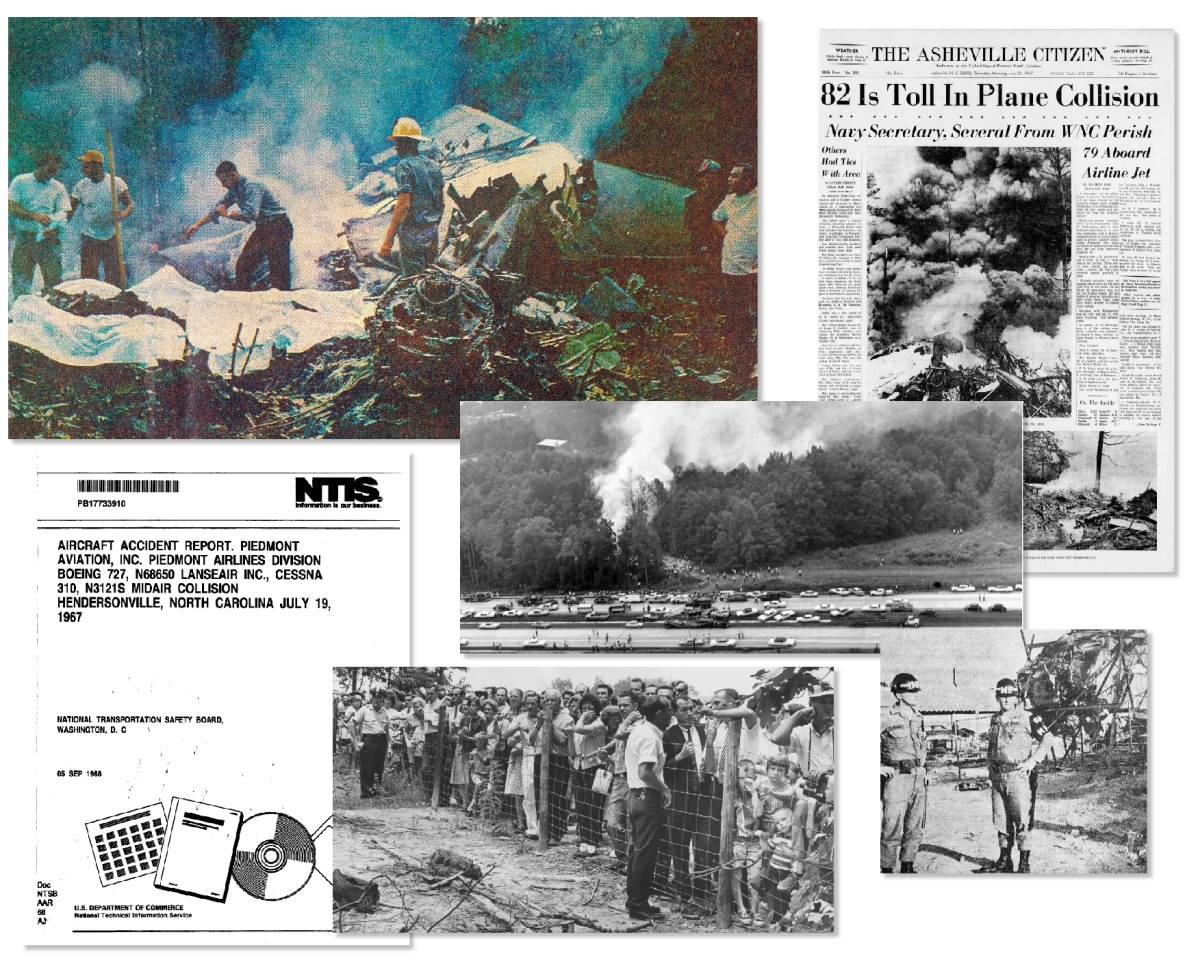

Looking back at the deadliest plane crash in North Carolina history, when 82 people were killed on Wednesday, July 19, 1967, after Piedmont Flight 22 collided with a Cessna 310 and both crashed in Hendersonville, NC.

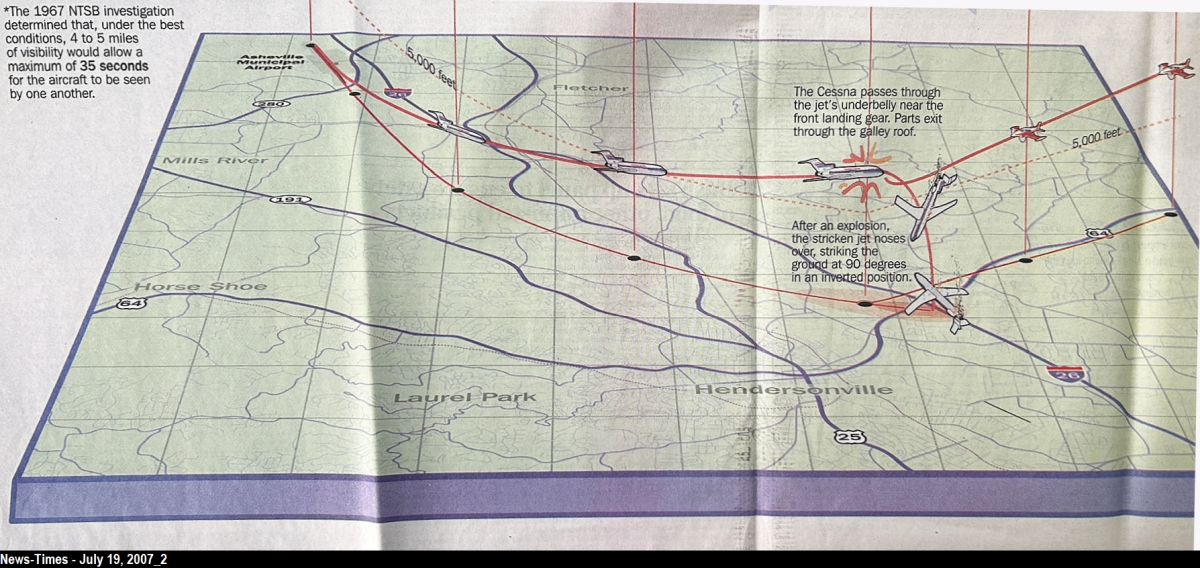

Piedmont Flight 22 was flying a Boeing 727 with 79 souls aboard. It had taken off from Asheville Municipal Airport at 11:58 a.m., heading to Roanoke VA. One minute later, it collided with a twin-engine Cessna 310 that was approaching for landing. There where three people aboard the second plane, which had been chartered from Springfield, MO.

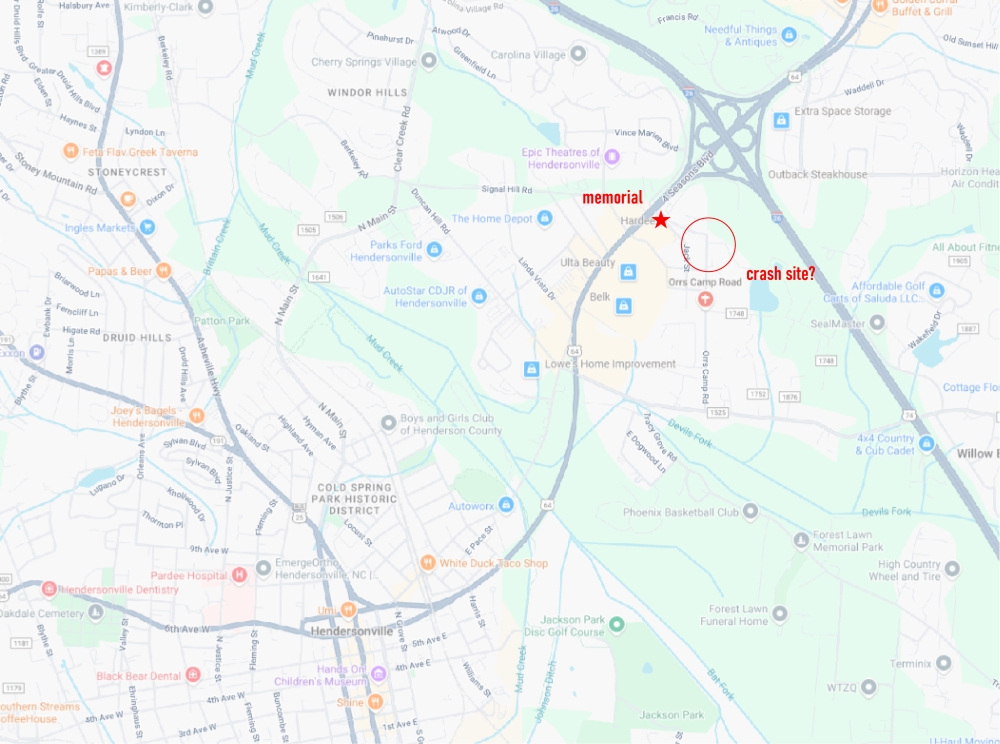

They were flying 6,132 feet and eight miles southeast of the airport when they collided at 11:59 a.m. Both were operating under instrument flight rules. The planes crashed just south of the intersection of Interstate 26 and Highway 64. The crash site was just 200 feet from the interstate. [AC, 7/20/67]

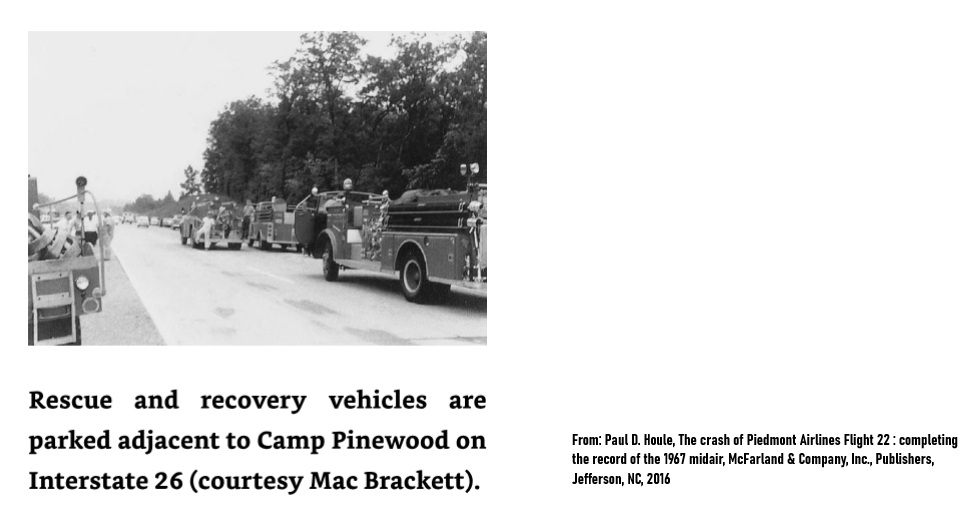

The main parts of the passenger jet landed in a wooded area at Camp Pinewood, a private summer camp for children near Interstate 26. It burst into flames upon impact. The crash site was near the camp’s archery rang, and near the camp’s trash dump. [WSJ, 7/20/67]

Other debris fell in nearby neighborhoods. One young girl was hit by debris at her home on Highway 64 about a mile from the crash site. She was not hospitalized. [AC, 7/20/67]

The wreckage of the two planes was spread over an area 1.5 miles long and a half-mile wide, along a path to the north and northwest of the impact point. The passenger jet was upside down when it struck the ground. The Cessna was severely fragment and only one identifiable portion was found at the main wreckage site. [NTSB]

The midair collision was also witnessed by dozens of people in the area, as jetliners were new to western North Carolina. Recalled one local resident in 2007, her two-year-old son loved watching the jets. He rushed to the window after they heard a large airplane flying overhead. [Times-News, 7/19/07]

Hundreds more turned their heads skyward when heard the midair collision. Among those watching were guests at a nearby 100-unit Holiday Inn, located about 2,000 feet from the crash stie. [AT, 7/19/67; AT, 7/20/67].

Windows in nearby buildings were also rattled by the initial explosion, witnesses later reported.

Some saw bodies falling from the sky, including one that fell through the roof and into the living room of a house at 204 Orr Camp Road about a half mile from the crash site. [AC, 7/20/67; AT, 7/20/67] The body of a uniformed stewardess was found on the median strip of Interstate 26, reported the next day’s Winston-Salem Journal. [WSJ, 7/20/67]

Numerous volunteer firemen worked at the nearby General Electric plant, or at mills in the area. The crash happened at the start of their lunch break and many saw the crash and “sped towards their fire stations to respond.” “Within minutes, all available rescue workers in every town and community within driving distance” was speeding toward the crash. [PH]

Fire and Rescue Response

Responding fire and rescue agencies included the Henderson County Rescue Squad, all Henderson County fire departments, and unit from neighboring counties. The longest recorded fire/rescue response was from 75 miles away in Belton, SC.

Fire department on scene included Hendersonville, Fletcher, Blue Ridge, Saluda, Etowah Horseshoe, Edneyville, Valley Hill, Mountain Home, Green River, and Asheville (Buncombe County). [MS]

Asheville Engine 5 responded, travelling some 28 miles. They were dispatched at 1:15 p.m. and returned to their station at 3:48 p.m. They used 20 gallons of water from their 1958 American LaFrance pumper. [RN]

Reported news accounts, crews had controlled and/or extinguished the fires within a half-hour of their arrival. And firefighters were spraying water and “chemicals” on the fire at least 90 minutes after the crash.

Two acres of the 53 acre camp ground were estimated to have burned, noted the next day’s Asheville Citizen. And trees as high as 75 feet were burnt black. [AC, 7/20/67]

Though Henderson County had only one rescue squad organization, there were over a dozen in neighboring Buncombe County. Many likely responded to the scene. In 1967, Buncombe County rescue squads included Bernardsville RS, Beaverdam FS, Black Mountain RS, Buncombe County RS, Enka RS, Fairview RS, and Skyland RS. Most were operated in conjunction with the community’s volunteer fire departments. [ML]

Ambulances at the scene included at least two from West Funeral Home in Weaverville in Buncombe County. [RN] Both ambulances and hearses would be used to transport bodies from the crash site to the temporary morgue.

City, county, and state law enforcement officers responded to the scene. Henderson County Sheriff J. F. Kilpatrick told that day’s Asheville Times that “every off-duty and reserve officer had been sent to the scene.” [AT, 7/19/67]

Law officers also “kept a sharp look-out for looting of victims bodies,” reported the next day’s Asheville Citizen. Said a Henderson County Sheriff’s Department spokesman, “deputies chased one man who removed a watch” from a victim, but lost the thief. [AC, 7/20/67] There were no reported arrests for looting. [AT, 7/20/67]

Hundreds at the Scene

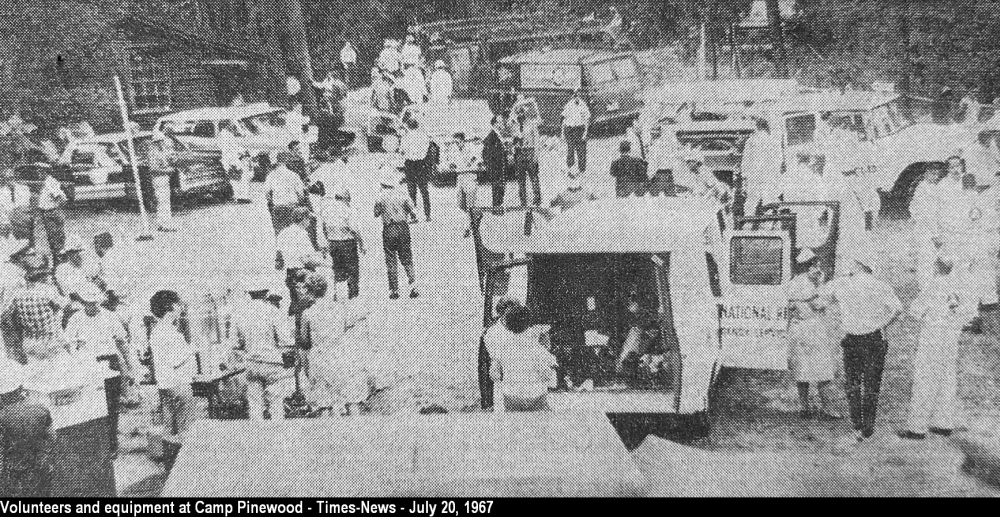

It was estimated that 200 rescuers and workers were initially at the scene. And some 400 rescue workers later searched for victims over a wider area.

They included 70 members of the North Carolina National Guard, members of Company B, First Battalion, 120th Infantry of North Carolina’s “Old Hickory” Division [WSJ, 7/20/67].

Others who assisted included firefighters, rescue squad members, Civil Defense personnel, private ambulance crews, law officers, and other volunteers.

At the time of the crash, local hospitals were alerted, local ministers reported to hospitals, and the American Red Cross sent two disaster vans and ten workers from Asheville. They also brought 60 pints of blood. Red Cross workers also set up canteen service for the emergency workers.

The FBI dispatched a “disaster team” to assist with identifying the bodies. [AC, 7/20/67]

Hundreds of curious citizens also came to the scene. Recalled one witness, she was amazed that she and hundreds of others were allowed to park alongside a major throughway and even walk to the crash site. [JL] The resulting traffic jam stretched all the back to Hendersonville, two miles away. [WSJ, 7/20/67]

Law officers erected a barrier about 200 feet from the main crash site, to stop spectators who came to the scene after stopping on the highway. They erected “multiple rope cordons,” noted the next day’s Asheville citizen, attempting to “screen the thongs.” But a “troublesome number of the idly curious” still got through. [AC, 7/20/67]

State highway patrol officers and sheriff’s deputies from Henderson and Buncombe county kept the slow-moving cars moving on the nearby roads.

A temporary morgue was established at the National Guard Armory in nearby East Flat Rock [WSJ, 7/20/67], where the victims were brought for identification. The high school gym was also used as a morgue. Noted one news account, some bodies were charred, others were note. [AC, 7/20/67] After each victim was examined, they were moved to refrigerated trucks parked outside.

Over the days that followed, emergency personnel searched for and removed victims from the crash site. Later, some 200 Boy Scouts were enlisted to help search the area for small pieces of the planes that had not been recovered.

The local WFW assisted by setting up rest areas for the workers in their building on Main Street, while ladies auxiliary members began preparing food for the workers. [JL] They served foot from several “comfort wagons.” [AC, 7/20/67]

The Henderson County chapter of the Red Cross also issued a call for vacant rooms, where families of the victims could be housed locally. [JL]

Other Stories

Henderson County Rescue Squad member Grady Walker lived nearby and saw the collision. He ran to the camp and directed campers to get away from the crash site. He told them to take cover as secondary explosions started. [MS]

He and the camp counselors may have saved some lives that day. There were 145 children between the ages of 6 and 14 attending the eight-week summer camp. None were injured. [AC, 7/20/67]

Because of their Civil Defense training, the rescue squad was later tasked with leading the recovery effort. [MS] And/or was supervised by state highway patrol Lt. K. B. Kuykendall, who was aided by the county sheriff. [WSJ, 7/20/67]

The owner of a nearby service station on Highway 64 reported “good business” to the next day’s Winston-Salem Journal, noting he normally closed at 10:00 p.m. but planned to stay open all night. The station stayed busy with spectators who refilled their cars and “dined from the vending machines.” [WSJ, 7/20/67]

Other Notes

Witnesses said the planes were still intact when they fell from the sky.

Others observed pieces of metal raining down from the sky, about the size of seats.

Two bodies, seats from the jets, and engine parts were found on the side of Highway 64 near Thompson Street. [AC, 7/20/67]

At a nearby home, a body fell through the trees and landing in the yard where the homeowner’s daughter was playing. On the roof of his home, an airplane wheel landed. [AC, 7/20/67]

Those first-arriving at the crash site heard two loud explosions after they got there.

But rescuers couldn’t reach the main impact area due to the intense heat from the fires. [AC, 7/20/67]

The jetliner fell across a large telephone line, severing service to some three thousand customers. [WSJ, 7/20/67]

A high wire fence separated the crash site from “thousands of people who packed four to eight deep” along the fence. [AC, 7/20/67]

Camp Pinewood was later used as a base of operations for collecting the bodies of the crash victims.

By that evening, a 17-person team of NTSB investigators arrived from Washington. They planned to lease a warehouse to store some of the wreckage. [AC, 7/21/67]

By Thursday, the day after the crash, officials had interviewed more than 50 people who witnessed the collision. The NTSB used 69 specialists split into six teams to talk with witnesses. [AC, 7/21/67]

On Saturday, the wreckage was moved by a local contractor who supplied flatbed trucks and a crane. [AC, 7/22/67]

Investigations

The crash was one of some 95 commercial air crashes worldwide that year, and the second-deadliest in the United States at the time. [Wiki]

The investigation was the first major investigation conducted by the newly created National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), which replaced the Civil Aeronautics Board. The resulting report, adopted on September 5, 1968, placed primary responsibility on the Cessna pilot. [Wiki]

The probable cause was the Cessna’s deviation from its IFR-cleared flight path and into the airspace allocated to the passenger jet. Minimum control procedures used in the handling of the Cessna were a contributing factor. [NTSB]

In 2006, the NTSB reopened the investigation to review possible irregularities identified by historian and former military traffic-accident investigator Paul Houle. He spent several years investigating the accident. [Wiki]

He cited his perceived problems with the investigation, including that the original report did not mention a fire in a cockpit ashtray of the 727 that commanded the attention of the crew for 35 seconds before the collision. The NTSB later upheld its original findings. [Wiki]

Other Information

The Boeing 727 was the first passenger jet operated by Piedmont Airlines. It and a second Boeing 727 Pacemaker were placed in service March 15, 1967, when the airline started its jet service. Both were leased from Boeing. [AP/Durham Herald Sun, 7/20/67]

The jetliner was named the “Manhattan Pacemaker.”

On a related note, it had been previously damaged by a car on May 25, 1967, on North Liberty Street, while it was being towed to a hangar. A women failed to see signal lights or the flagman. She was hospitalized, the top of her car was flattened, and the plane suffered $25,000 worth of damage. [AP/Durham Herald Sun, 7/20/67] Read that story.

The crash was the third fatal crash in the airline’s history, after a DC-3 that crashed in Charlottesville, VA, on October 31, 1959, killed 27 people with one survivor, and a Martin 404 near New Bern, NC, on November 21, 1966, that killed the three-person crew. No passengers were aboard. [TCS, 7/19/67]

Aftermath and Legacy

Victims’ families filed 16 lawsuits seeking nearly $11 million in damages against Piedmont, Lanseair [the owner of the Cessna] and others.

On July 17, 2004, a memorial marker was dedicated. It’s located a quarter mile from the crash site and lists the names as they appeared on the flight manifest sheet. The final three names are those aboard the Cessna. The project was led by the Western North Carolina Air Museum.

Sources

Various newspaper articles:

- AC – Asheville Citizen

- AT – Asheville Times

- TCS – Twin-City Sentinel

- WSJ – Winston-Salem Journal

Plus:

- JL – Jeanne LaGranne, “Just Couldn’t Happen Here! But it did”, date and publication TBD.

- ML – Mike Legeros research.

- MS – Mark Shepherd, The Crash of Piedmont Flight 22, May 31, 2017, Henderson County Heritage Museum posting on Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/share/1FqjBnmsVW/

- NTSB – National Transportation Safety Board aircraft accident report, adopted September 5, 1968.

- PH – Paul D. Houle, The crash of Piedmont Airlines Flight 22 : completing the record of the 1967 midair, McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, NC, 2016

- RN- Research notes from a retired member of the emergency services community, created in 2017, https://legeros.com/history/library/disasters/hendersonville-1967.pdf