View clippings and other documents

Introduction

On Saturday, September 26, 1969, a methane explosion and flash fire at the National Guard Armory on Silas Creek Parkway in Winston-Salem injured 25 members of the North Carolina National Guard. Seven of the most seriously injured were flown to an Army burn center in Texas. Three later died.

Of the 22 remaining injured guardsmen, nine were hospitalized for long periods and eventually declared 30 percent to 100 percent disabled. They were all awarded full disability benefits by the federal government.

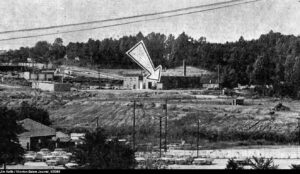

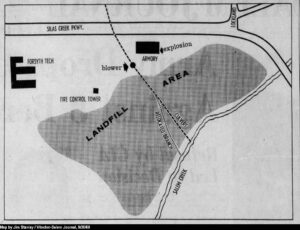

The explosion was caused by colorless and odorless methane gas created by decaying garbage at the nearby sanitary landfill. The armory was located less than 100 yards from the landfill. And there had been at least two prior explosions in the vicinity of the city landfill but none that had caused serious injuries.

The emergency response included the Winston-Salem Fire Department and a dozen or more ambulances including the county ambulance service, local rescue squad ambulances, and funeral home ambulances. Plus, numerous police officers, some who transported patients in their patrol cars. The city police academy was also located in a building that adjoined the armory.

The armory was also located near the fire department drill tower and training grounds, which were also adjoined the old landfill site.

Timeline of Events

Friday, September 25, 1969

“City officials” responded to the armory to investigate a possible gas leak. They did not find any leaking gas. The problem had been reported for a number of days, with guardsmen reportedly getting woozy and having trouble breathing in the supply room. There was a weekend drill planned at the armory starting the next day. Officials agreed that the drill could proceed as scheduled. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

Saturday, September 26, 1969

07:30 a.m. – Estimated 300 members of the 230th Transport and Supply Battalion reported for annual firearms practice at the armory’s indoor shooting range. [TCS, 9/27; N&O, 9/28/69]

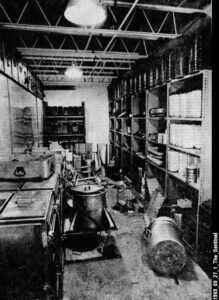

08:40 a.m., just before – More than 300 men were inside the armory. Just before the explosion, eight or ten men were inside the supply room “to the large drill hall.” Some of them were cooks getting kitchen equipment, said one initial report. Later, news stories reported that they were picking up their weapons before heading to the firing range. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

08:40 a.m. – Explosion flashed through the supply room as the guardsmen were preparing to draw weapons. It produced mostly heat and little fire.

Notes on the explosion:

- It “seared walls and ceilings” of the supply room.

- It slammed shut and locked the door of the supply room. It also blew out windows.

- When a key was found and the supply room door was unlocked and opened, “heat and dark blue flames came out of the door” and “singed several people standing five to fifteen feet away.”

- It lifted the southeast corner of the roof eight inches off the building.

- It was felt across the 2000 block of Silas Parkway.

- The heat in the room reached 1,200 degrees in the moments after the explosion, Assistant Fire Chief James Parham estimated.

- But the flames “roared only momentarily before they died down.”

- Source: [N&O, 9/28/69]

Notes on the victims:

- Uniforms were burned as men “stumbled from the supply room.”

- Fellow guardsmen rushed to the burned men and wrapped them with blankets.

- By the time the first firefighters arrived, the injured had been “laid out on the drill hall floor” and were receiving first aid from other guardsmen.

- Source: [N&O, 9/28/69]

Notes on the cause:

- The explosion was caused by colorless and odorless methane gas produced by burning trash at the nearby sanitary landfill.

- The landfill was located less than 100 yards from the armory.

- The explosive gas had spread underground beneath the armory.

- Recent rain and fog had trapped the gas fumes, explained Chief Parham, and prevented them from mixing with fresh air in the atmosphere, which would render the fumes harmless.

- Fumes seeped through “jagged cracks in the cement floor” and into the supply room and were ignited by a spark.

- The spark could have been caused by anything, such as the scraping of a shoe sole with an exposed nail.

- Source: [N&O, 9/28/69]

Notes on the response:

- Officials summoned “all available ambulances, firemen, and police.”

- A dozen or more ambulances responded, including county ambulances, local rescues squads, and “private funeral cars.”

- Less seriously injured victims were transported to hospitals in police cars.

- Police also quickly “sealed off intersections and directed rescue vehicles.”

Later events:

- At 10:00 p.m., Fire Captain D. R. Hasting, who was conducting the fire department’s investigation, said there there had been “no significant increase of gas in the armory.” [WSJ, 9/28/69]

- Hastings said firemen would continue “monitoring the gas level” at two-hour intervals through the next day. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

- The armory building would “remain open and fully ventilated through the night”. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

Notes on the site:

- Adjoining the armory was the two-story police academy building. There were no immediate plans to close the building. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

Sunday, September 27, 1969

06:30 p.m. – US Air Force C-9 medical transport plane landed at Smith-Reynolds Airport. It arrived to receive seven of the most seriously burned victims and several wives. Their destination was Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, TX, and the Brooke Hospital burn unit. The flight was two hours. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

08:15 p.m. – The first three victims arrived in ambulances from Baptist Hospital. They were carried on stretchers up a steel ramp and into the plane. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

08:30 p.m., or abouts – Four more patients arrived from Forsyth Medical Hospital. The special burn team from San Antonio, including surgeons Dr. Harold Burch and Dr. Paul Silverstein, along with two medics, board with them. Also aboard were two flight nurses and three air medical technicians. The plane was part of a medical squadron from Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. Inside the plane were steel frames to secure each stretcher. Each had a wall outlet for oxygen and vacuum suction. In the rear were 20 rear-facing passenger seats. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

08:40 p.m. – The plane closed its doors for departure. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

09:07 p.m. – The plane took off. “Flashing red lights from two fire trucks on hand” illuminated some 250 people watching from behind a railing, including family and friends of the victims, along with some 60 uniformed guardsmen, policemen, firemen, rescue squad members, and medical personnel. [WSJ, 9/28/69]

The Victims

October 10, 1969 – Spec. 5 Dalton K. Koontz, 27, died. He was seriously burned, with over 60 percent of his body burned. He had been under intensive care since the explosion and was conscious until the time of his death. He was survived by his wife and two children, ages 2 and 11. [WSJ, 10/11/69]

October 13, 1969 – Sgt. Robert M. Coltrane died. He had sustained burns over 76 percent of his body. He was survived by his wife, who was expecting a child within the next three weeks.

October 29, 1969 – Master Sgt. Joel Calhoun Jr., 39, died.

December 5, 1977 – The Sentinel – Of the 22 remaining injured guardsmen, nine were hospitalized for long periods and eventually declared 30 percent to 100 percent disabled. They were all awarded full disability benefits by the federal government. [TCS, 4/24/72]

Lt. Col. James N. Stoneman spent more than four years handling the “mountain of paperwork” and fighting for benefits for the injured and the families of those who died. The process required starting a separate investigation for each of the 25 men. He recalled he signing name more than 1,500 times over a three-night period. [TCS, 12/5/77]

For the three critically injured members, Stoneman ensured that they were retired on disability as quickly as possible. Two died on the day they were retired, and the other died the day after. [TCS, 12/5/77]

Admitted to Baptist and Forsyth Memorial and Later to Army Burn Center in Texas

- Johnny A. Naylor of Lewisville

- Joel Calhoun of Kernersville

- Dalton K. Koontz of Lexington

- William E. Batts of Winston-Salem

- Roland J. Gay of Winston-Salem

- Bodo Beer of Winston-Salem

- Robert M. Coltrane of Winston-Salem

Treated at Forsyth Memorial

- Daniel F. Craver of Winston-Salem

- Harold Dunevant of Winston-Salem

- Phillip Posey of Winston-Salem

- Steven A. Shore of King

- Johnny Musser of Thomasville

Treated and Released

- Steven Everhart of High Point

- Robert M. Clore Jr. of Winston-Salem

- Bobby R. James of Winston-Salem

- Clyde L. Fulk of King

- Ronnie L. Morgan of Pfafftown

- Arvil E. Robertson of Winston-Salem

- Robert G. Long of Winston-Salem

- Ronnie V. Lauten of Winston-Salem

- Robert E. Tuttle of Lewisville

- Samuel E. Marion of Pinnacle

- J. McKinney of Bath

- Boyce Beeson of Winston-Salem

- James A. Long of Winston-Salem

Earlier Explosions

After the explosion, city officials acknowledged at least two prior incidents where methane gas caused small explosions, but without serious injures:

- Two firemen suffered second- and third-degree burns on November 9, during a training sessions. A group of firemen were standing near a drain culvert. One lit a cigarette and tossed away the match. Gas that had settled in the drain system exploded. The two firemen were treated and released from the hospital.

- National Guard member was soldering a section of gutter and caused a small explosion around December 1, 1965. He was not hurt.

Source: WSJ, 12/6/65]

Aftermath

Then what happened? Selected headlines:

- “Armory May Close for Good” – TCS, 9/29/69

- “City to Bring In Consultants on Blast” – WSJ, 10/1/69

- “City Loses Explosion Immunity” – TCS, 3/16/72

- “Armory Blast Suit Rehearing Sought” – TCS, 4/25/72

- “Armory Suit Costs Mount” – WSJ, 12/10/72

- “Armory Explosion Trial Opens” – TCS, 8/20/73

- “State Official Says Landfill Did Not Meet Standards” – WSJ, 8/28/73

- “Suit Over Armory Blast Settled for $800,000” – WSJ, 8/29/73

- “Shopping Center May Be Put on Old City Landfill Site” – WSJ, 7/12/74

- “Old Landfill Site Cleared for Use” – TCS, 7/12/74

- “Former Link Road Landfill Site a Lawsuit Breeding Ground” – WSJ, 4/18/82

- “Commercial Development of Landfill Unwise, State Says” – WSJ, 4/18/82

- “City contracts to convert landfill gas to electricity” – WSJ, 5/10/94

- “Golfers’ driving range may be built over landfill” – WSJ, 5/13/94

Sources

- TCS – Twin-City Sentinel

- WSJ – Winston-Salem Journal

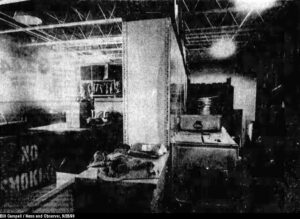

About The Armory

On June 14, 1962, construction bids were opened for a $220,000 joint-use facility that combined a National Guard Armory and police department academy. The armory would house the 230th Transportation Battalion and be located on eight acres on the south side of the new Silas Creek Parkway. It would replace the Guard’s current building at 940 Patterson Avenue, which the Guard had occupied since 1920. The police department would occupy a separate wing of the new building. [WSJ, 6/15/62]

The new armory was completed in the fall of 1963. It was dedicated on October 18, 1963. Noted one of the event speakers, the armory was one of about 500 in the country that were built since 1949. And there were plans to build about 400 or more additional armories. [WSJ, 10/19/63]

However, the Guard continued using the old armory on Patterson Avenue for its maintenance shop and for parking some of their trucks and Jeeps. By April 30, 1969, all of the Guard’s operations had been consolidated at the new armory and the old armory had been returned to the city. [TCS, 4/30/69]

The police department formally occupied its new training building on May 6, 1963. It was located in the west wing of the new armory, and included a large classroom, library, offices, an indoor shooting range, and a shop for reloading cartridges. The indoor shooting range was shared with the Guard. [WSJ, 5/7/63]

About the Landfill

The landfill opened in late 1949. [WSJ, 8/19/69] (But was there an earlier trash dump on the site, that opened in 1931?) [WSJ, 3/24/69]

By the late 1960s, nearby residents were complaining to city officials about the “offensive odor, flies and rats” associated with the facility.

On November 11, 1968, the city’s Public Works Committee recommended closing the landfill within six months.[1]

The methane gas was a particular concern to residents nearby. Some said the odor was so bad at times that they had to keep their windows tightly closed. Flies were also a problem, notably in the summer. “You can’t cook a hamburger or a steak, the flies will carry it off.”

They noted that much of the odor originated from methane gas, produced by the decaying garbage that was dumped at the site years ago. The gas collected in a “large 72-inch culvert under the filled-in area” and found its way into the atmosphere.

It was also noted that the problem of methane gas was long-term and would continue even after the landfill was closed.

It was also noted that there had been three or four small fires at the landfill recently, requiring much of the compacted trash to be dug up, which produced a strong odor and required some 400,000 gallons of water to be sprayed on the smoldering fires. [WSJ, 11/12/68]

[1] However, the landfill remained open due to difficulties finding an alternate site.

More Pictures