He was the first man up in the morning, and the last one to bed at night. Three times a week the horses were taken out at 5 a.m. for exercise, unless they had run the night before. This meant the driver got up at 4 a.m. There were stalls to clean and horses to groom and harness to polish. This all had to be finished by 10 a.m. Otherwise 6 a.m. was the usual rising hour for all firemen. Upon rising, the driver curried and brushed his horses, while another scrubbed down the stalls with boiling water, and a third man took care of the harness. Still others took care of the specific feeding routine.

Each fireman who had the care of a horse went back to do his final chore for the day before retiring. He cleaned the stall floor, and bedded it with straw or peat moss. He filled the wire basket with hay, and put water in the basin on the left wall. Also, at 10 a.m., every morning there was uniform inspection, and examination of quarters, horses, and apparatus. During these inspections the men stood at attention, while the captain walked about. If all was satisfactory, the men were saluted and were released to go at will to quarters.

They looked forward to the leisure time after inspection. Unless they were called, their time was their own, to do as they wished. Some slept, others read, and almost always there was some kind of card game in progress.

They worked twenty-four hours a day under the old system, with only one day off each month. The hours were long and tedious. The driver had the day watch from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., the lieutenant from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. Then the night watch was given over to the regular firemen on four-hour shifts.

The main floor was dark save for a small lamp on the watch desk and the lanterns that hung, one on each side of the hose wagon, steam engine, ladder truck and chief’s carriage. The signal gongs and wall telephone that linked the firehouse to headquarters and to every corner and alley in the city, and the automatic switching, levers, and push buttons that operated the various alarms, release devices and house lights in the station, were all in the compact space against the wall toward the front of the room.

There sat the man on watch, at a tilt-top desk on which the journal lay opened and ready to take the record of the next alarm. He sat alone at the desk. The house rules kept all the other firemen upstairs or out in the yard, except when there was an alarm or fire, or when they had some station duty to perform.

Turned down boots stood waiting in pair about the floor, rubber coats, with insides up so the sleeve holes could be found in a hurry, hung conveniently over knobby parts of the apparatus. Between the hose wagon and the ladder truck was the chief’s black carriage, small, delicate. Over the dashboard hung the chief’s white coat and while helmet and the driver’s cap and jacket.

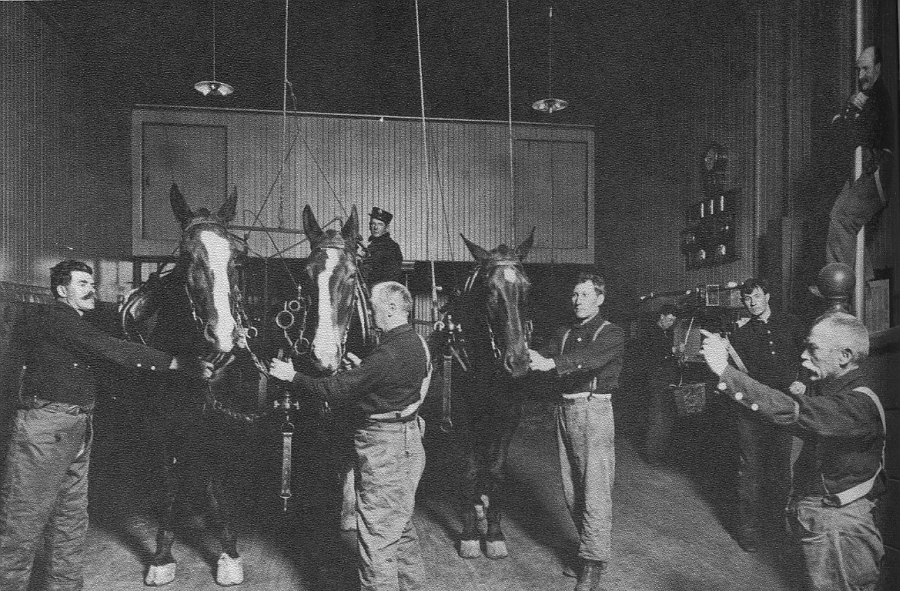

At unannounced times, the assistant chief made rounds of the house to look over the horses. He would pull a white silk handkerchief from his pocket, and rub it over the back, neck, and sides of the horses. Any slight soil on the silk was serious; a real offense. A complaint about the horse of the horses meant a fine of at least ten days’ pay. Cleanliness was important, but much attention was also paid to the feet of the animals. Without good, healthy feet a horse was useless. Shoes were changed approximately every four weeks.

A weekly inspection was held, in the old horse-drawn apparatus days, to determine how quickly horses could be harnessed to the engines. The battalion chief of the district stood with a stop watch in his hand and checked the time. A firehouse’s reputation was only as good as its horses and men.

If it took more than twelve seconds for the men to harness up and be at the curb line of the street, it was considered poor time. One might say here that they rolled out of quarters quicker with the horses than they do with the motor apparatus today. But today, of course, the time is made up on the road.

A competitive, or speed test was held on April 22, 1893, to ascertain the exact time in which one man could dress, harness the horses and have the engine in the street after the gong sounded. At this test, Lemuel Rudolph of No. 7 Engine, carried off the prize […] by making a hitch in 25 ½ seconds.

Selected excerpts from The Firehorses of San Francisco by Natlee Kenoyer. Published 1970 by Westernlore Press, Los Angeles, 94 pages.

Photo – Engine No. 11, San Francisco Fire Department. A call out at night, April 1914. Courtesy San Francisco Fire Museum.