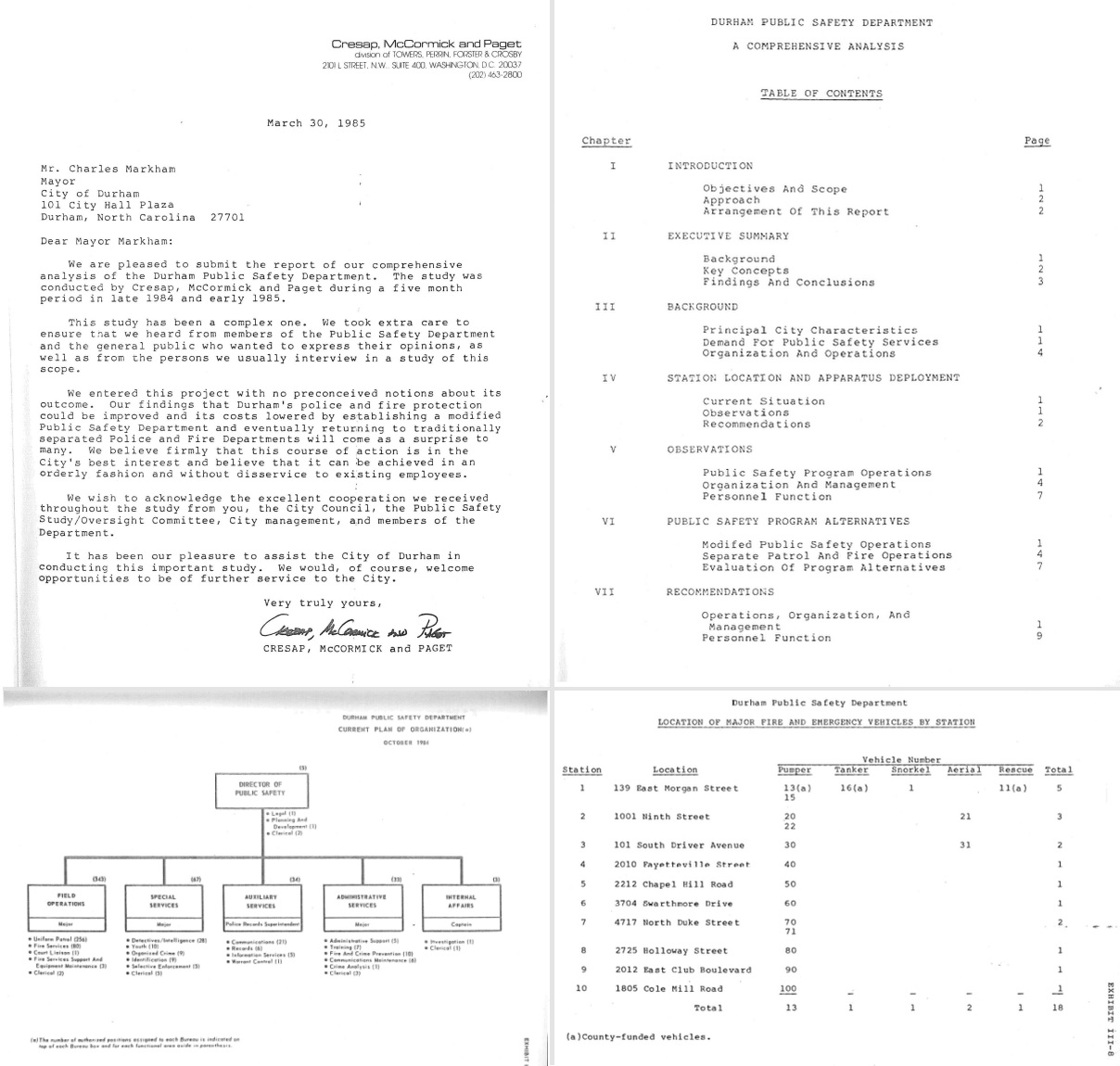

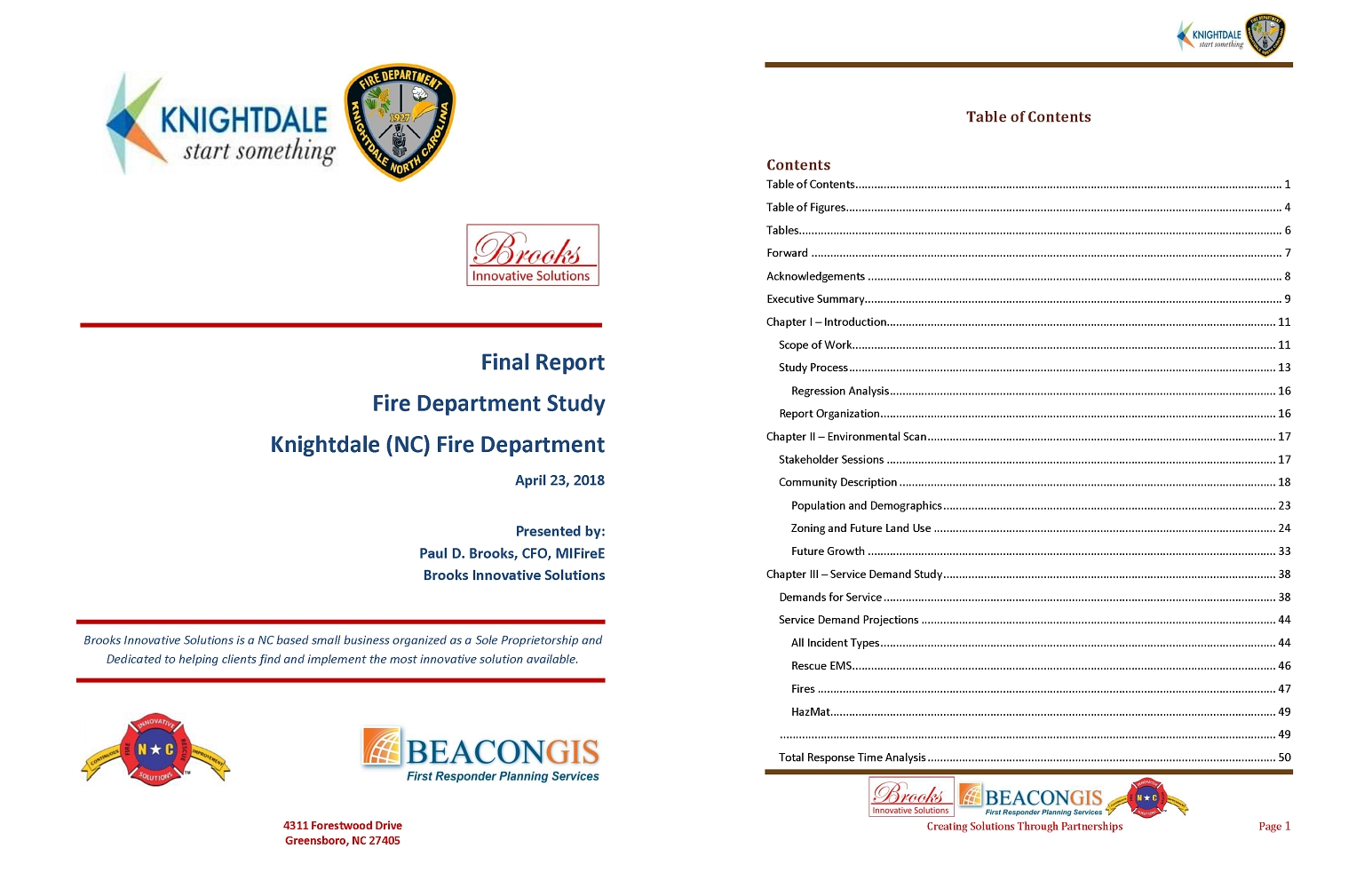

Found these plane crash photos from 1978 by Jim Thornton in the Herald-Sun photo collection at Wilson Library at UNC. Here’s the story behind them.

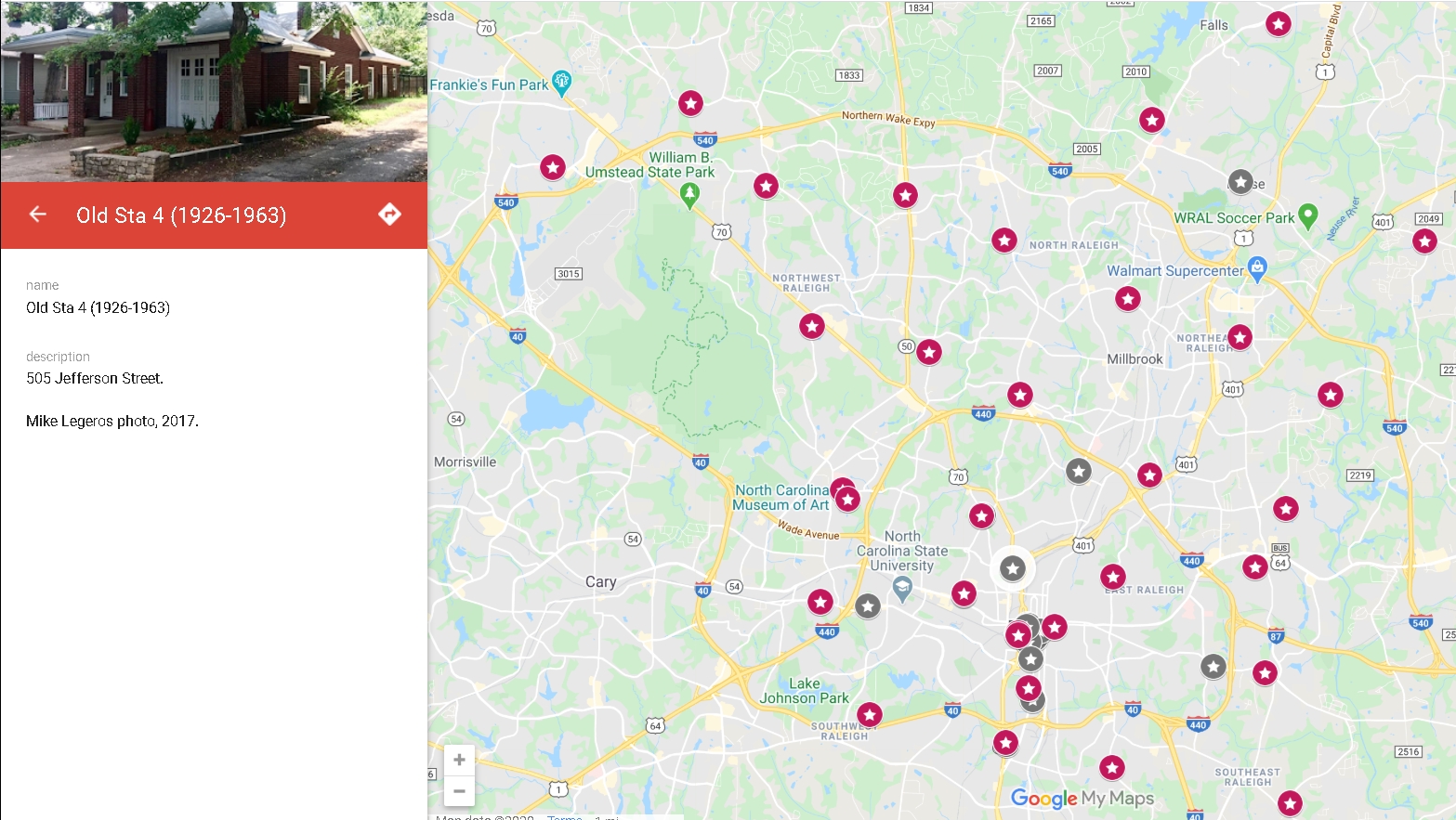

On Monday night, February 13, 1978, a twin-engine Aero Commander 600 approaching Raleigh-Durham Airport disappeared from radar at 8:00 p.m. Six souls were aboard. The plane apparently struck a tree and crashed about two-and-a-half miles southwest of Runway 5-23. And though it crashed just a few hundred yards south of Interstate 40, it took rescuers almost five hours to find the two survivors.

The aircraft crashed at 8:02 p.m., reported the NTSB, and into a “swampy area” south of the airport. Upon impact, it also began transmitting an automatic distress signal.

Alerted to the possible plane crash, the airport fire department responded and with their new full-time personnel. RDU CFR had recently hired thirteen new people to provide full-time staffing during the hours that commercial flights were arriving and departing. This was a significant upgrade of the airport’s crash-fire-rescue capabilities, and ended improvements started in summer of 1976, after unfavorable news stories began asking uncomfortable questions about the airport’s emergency response capabilities.

Prior to the department’s overhaul, RDU firefighters also had other airport support duties, notably performing refueling operations for private airplanes. There were questions of adequacy of training, staffing, and equipment. Among the improvements in late 1977 and early 1978 included a new ARFF crash truck, a new quick-response unit with a dry chemical skid system, and new communications and radio equipment. The chief of department was Terry Edmundson, former Fire Chief of Cary.

Read more about RDU CFR history at www.legeros.com/ralwake/rdu/timeline.shtml. See historical photos from that era at www.flickr.com/p…/raleighfiremuseum/albums/72157691054681296

Hundreds of Searchers

Back to the night of February 13. Mutual aid to the incident was extensive, with what one newspaper called “virtually every volunteer [responder] and emergency unit in the area.” That included Morrisville FD, Parkwood FD, Cary FD, Yrac FD, Durham Highway FD, Cary Rescue, Parkwood Rescue, Wake County EMS, Durham EMS, the State Highway Patrol, Wake County SO, Durham County SO, and the Civil Air Patrol.

As was the airport’s standard operating procedure, they notified the Civil Air Patrol, which launched a search plane. However, the search plane couldn’t fly low enough to pinpoint the crash site. Also, the search plane’s automatic distress beacon inadvertently began transmitting, and caused confusion.

The Coast Guard was contacted and sent a helicopter from Elizabeth City. It located the crash site from the downed craft’s homing beacon around 11:50 p.m. [ Let’s guess 60 to 80 minutes flying time from Elizabeth City to Morrisville. ]

By the time the helicopter had located the crash site, some 300 searchers were participating, including private citizens who joined after hearing about the crash on their CB radio. But the searchers had been hampered by fog and swampy, wooden terrain. Reported one account, the terrain was wet and icy, and rescuers walked in water ranging from knee to waist high.

Once the helicopter located the wreckage, a command post for all search parties was established “on the highway.” [ Was that on the Interstate 40? Or on Airport Road or Sorrell’s Grove Road? ]

Wreckage Found

About an hour later, members of the search party spotted the plane. It was found about 12:50 a.m. There were two survivors, adult males, one of whom was found wandering several hundred yards from the crash site either ten minutes before or after, depending upon the news report.

He was admitted to Wake Memorial Hospital for severe frostbite on both legs and multiple abrasions and cuts. He had apparently been thrown from the plane as it fell.

The other survivor was found pinned inside the airplane, which reportedly crashed upside down at full-power. He was treatment for multiple abrasions and a cervical fracture. The other four adult males aboard died of massive injuries, reported the assistant state medical examiner.

News accounts noted that at least $20,000 was found in the wreckage, along with about two pounds of marijuana, and a “small quantity of powdery substance.” The six men aboard were most (or maybe all?) in their twenties. The plane was travelling from Bedford, MA, to Monroe, NC.

Disaster Plan Needs Update

Three weeks later, the News & Observer published some after-action accounts of the incident. The rescue crews had used the airport’s “forty-page disaster plan” for the incident. However, as the newspaper noted, the document contained “scant references to searching for a downed plane.” Instead, it “merely suggested calling for search planes from Civil Air Patrol, Coast Guard, or military.”

The Raleigh-Durham Airport Authority passed a resolution the prior week, calling for a search plan to be written and coordinated with the disaster plans of Wake County Civil Preparedness office. However, the county plan also didn’t include preparations for downed planes [outside of the airport]. Noted Director Russell Capps, they were considering adding that to their plan.

Why didn’t the airport’s disaster plan include instructions for searching off-property? Because the FAA required that disaster plans be limited to incidents on airport property. The limits were imposed because the FAA recognized that some airports disagree with adjoining communities, over who takes charge when a plane crashes near the boundaries of an airport.

And there were other issues cited by the newspaper. When any plane fails to land, the control tower notifies Civil Air Patrol, which “sends off” a search plane. But because CAP isn’t requested by RDU-CFR, the two groups don’t coordinate. Radio interoperability was also an issue, with RDU-CFR unable to talk to sheriff’s departments participating in the search and could only communicate indirectly with search planes via the control tower.

And then what happened? To be determined. This is where our story ends for today.

Jim Thorton photos, February 15, 1978. From Box 1_04_55, in the folder Aircraft Accidents, in the Durham Herald Company Newspaper Photograph Collection #P0105, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sources include:

Durham Sun, February 14, 1978

Durham Sun, February 16, 1978

News & Observer, February 14, 1978

News & Observer, February 15, 1978

News & Observer, February 16, 1978

News & Observer, March 6, 1978.