This is a version of an earlier Facebook posting.

Scenes from a community meeting at New Hope Baptist Church on Monday night, May 9, 2022, to inform and answer questions about a new city-county partnership. On July 1, 2022, the city of Raleigh will begin covering the response district of Wake New Hope Station 1. Wake County Fire Services Director Darrell Alford gave a great presentation on same, and fielded questions along with Wake New Hope Fire Chief Lee Price and Raleigh Fire Chief Herbert Griffin.

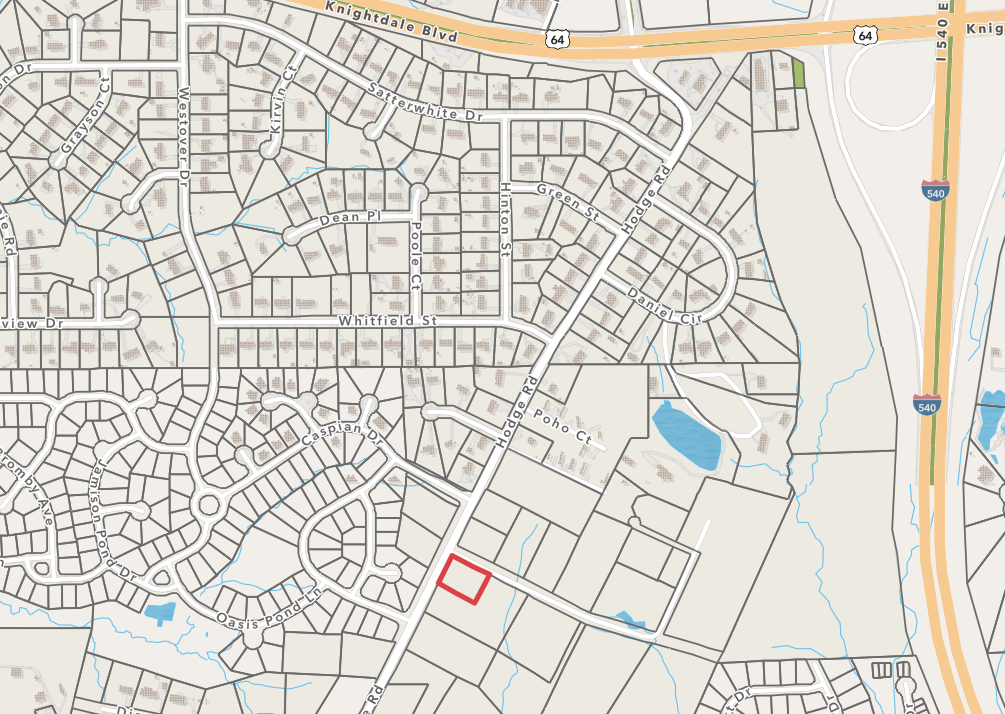

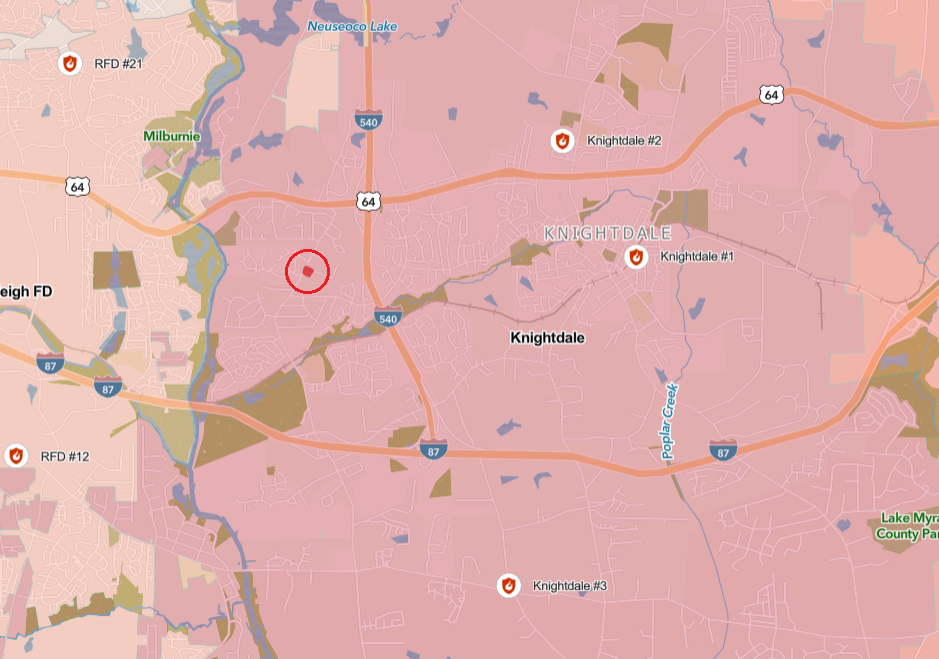

The response district dates to 1958, when Wake New Hope FD started service. The current Station 1 service area has undergone dramatic changes since the late 1950s, and most of the area has been annexed by the city of Raleigh.

Less than five square-miles of unincorporated area remain in the Station 1 district. By the numbers, that’s 4.69 square-miles with 1,244 occupied housing units and a population of 3,280 people. The property value is estimated at $489M and it had 247 fire/EMS calls in calendar year 2020. And, of important note, there are five Raleigh fire stations within five miles.

Continue reading ‘Wake New Hope Community Meeting – May 9, 2022’ »